A brief history of video game censorship in Singapore

What do arcades, Half-Life and Mass Effect have in common?

What do arcades, Half-Life and Mass Effect have in common? All of them were at one point banned in Singapore. From the early 80s to today, this brief history of video game censorship explores how Singapore's restrictions were shaped by backlash, industry and the press.

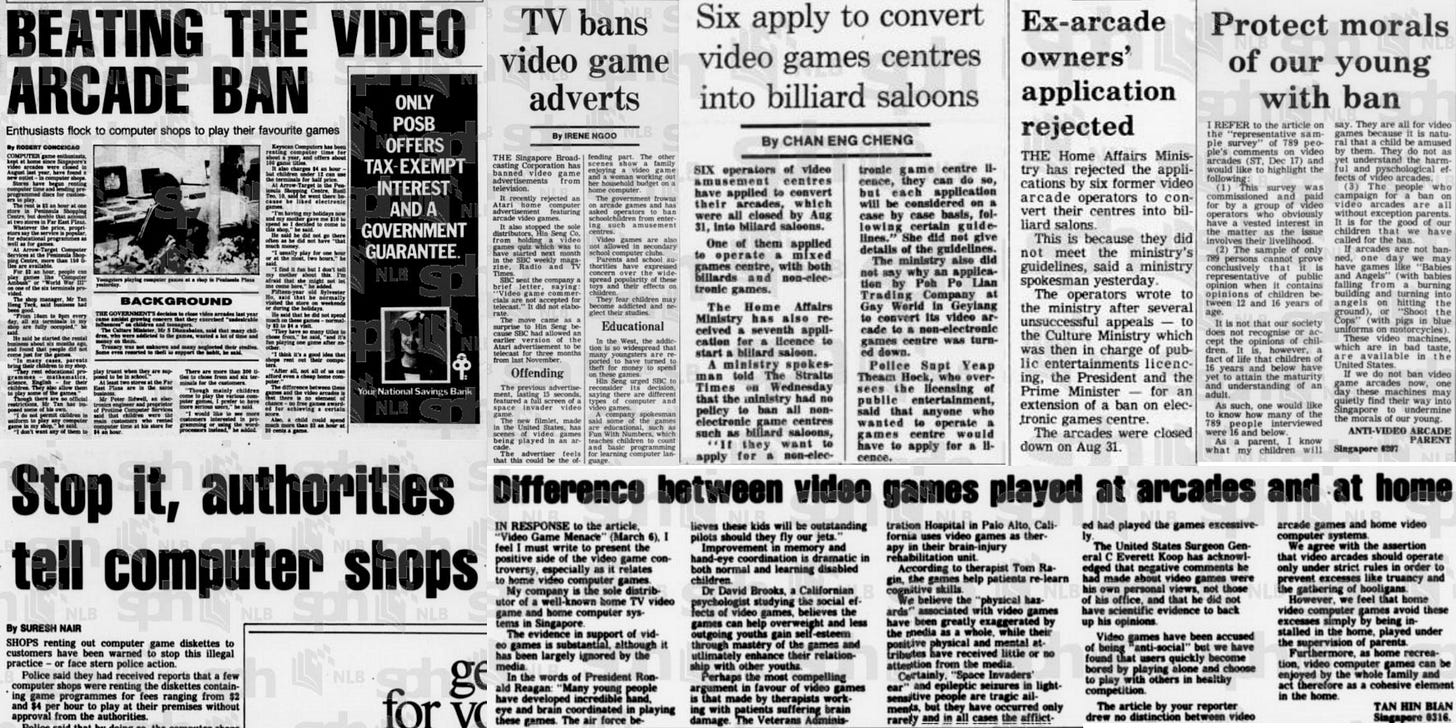

1983: “Protect morals of our young with a ban” — Anti-Video Arcade Parent

As the popularity of arcade games was booming across the world, Singapore was busy imposing a nationwide ban on arcades, reportedly because of parental concerns over video game addiction (some things never change).

The 80s were tough times for arcade operators, who had to sell off their assets and close up shop. When some of these operators applied to convert their arcades into billiards saloons, their applications were rejected by the Ministry of Home Affairs.

These were also interesting times for video game enthusiasts, who wrote letters justifying the value of games to an occasionally hostile public. In response to an article entitled “Video Game Menace”, one writer explained how video games can improve motor functions, and sought to distance home video games from the “truancy” and “hooligans” associated with arcades.

A year later, video game enthusiasts were finding creative ways around the ban. Beyond playing video games at home, enthusiasts who lacked computers at home could also rent time at computer terminals in shops, at rates ranging from $2 to $4 an hour. It is worth noting that these early internet cafes predate the world's first official internet cafes (which started in the US and UK around 1991 and 1994).

By the 90s, the ban on arcades had been lifted and had given way to a thriving arcade scene — so the video game enthusiasts clearly had the anti-gaming parents beat.

1994 Onwards: Singapore vs Violent Video Games

New censorship guidelines on video games were introduced by the government in 1994, prohibiting video games from showing sadistic acts or excessive violence. One of the most well-known casualties of this new censorship regime was Mortal Kombat, a fighting game known for its comically over-the-top finishing moves.

In 1996, Singapore's Board of Film Censors was raiding shops to seize copies of Mortal Kombat 3. How impactful these raids were is unclear, with some media reports from this time mentioning piracy as a workaround to the ban. This writer can only imagine what it must have been like to live in a time when Mortal Kombat was a controlled substance.

Such raids and seizures reportedly continued even into the early 2000s, when video game censors banned Valve’s blockbuster video game Half-Life and raided LAN shops to remove the game from their computers. By this time, however, public backlash and outrage towards the authorities’ attempts to control video games had become more commonplace.

According to Gamestop, this ban on Half-Life and its offshoots (such as Counter Strike) lasted for only a week before being overturned, reportedly “because the game had been released for more than a year” but likely due to local outrage: in the span of that week, Half-Life Asia’s petition to save the game accumulated thousands of signatures.

2007: Singapore's Censors say No to "Lesbian Intimacy"

Bans on video games continued into the late-2000s, with the state banning God of War 2 for nudity and The Darkness for its violence and offensive religious content.

However, the most well-known instance of video game censorship came in 2007, when Singapore's Media Development Authority banned Mass Effect. The deputy director of the Board of Film Censors released a statement explaining that the game had been banned because it featured a scene with “lesbian intimacy” between a human and alien woman.

Singapore instantly made international headlines for being the only country in the world to have banned Mass Effect. This ban was extremely short-lived, ending less than a week later, after intense local and international outrage.

While brief, the ban and surrounding controversy may have had a lasting impact. For the Mass Effect series of games, reports indicate that the massive controversy over Mass Effect’s same-sex love scene was a reason for why same-sex romances were cut from the second game of the trilogy.

This ban also had a longer-term impact on Singapore. Mass Effect was the last high-profile video game ban in Singapore in the 2000s, and the controversy over it would come to play an important role in the authorities’ decision to introduce a new and less controversial system for defining acceptable content in video games.

For more stories on Singapore's internet, press and government, subscribe to receive email updates with each new issue's release.

2008: “A global media city with forward-thinking systems that are beneficial to everyone”

After the backlash to its ban on Mass Effect, the Media Development Authority announced in 2008 that it would focus more on video game ratings and industry co-regulation. Such ratings would give regulators the ability to limit access to games based on age or call for alterations to games instead of banning them — though the MDA could still choose to refuse classification and ban a game.

Backlash to the ban on Mass Effect played a key role in this decision. According to a Today op-ed by Tech Editor Ariel Tam, although the MDA quickly overturned the ban,

“... the damage was done — Singapore was derided as a repressive nation with hair-trigger regulations and anachronistic sensibilities, and local gamers found it hard to hold their heads high within the global gaming league.”

Such a negative image also went against ongoing efforts to build up Singapore’s video game industry. Drawing multinational video game corporations to Singapore using tax breaks and other incentives was a key priority of Singapore’s Economic Development Board (EDB) during the late-2000s, as it sought to make Singapore a capital of digital media development. The most prominent examples of this include Ubisoft, Electronic Arts and LucasArts.

Singapore Samizdat understands that the EDB’s office displays a sculpture of an iconic location from Ubisoft’s blockbuster Assassin’s Creed series of games. Ubisoft opened its Singapore office in 2008, a development that was reportedly based on strong support from the Singapore government.

Thus, as another Today article puts it, the introduction of the video game rating system “puts Singapore one step closer to transforming itself into a global media city with forward-thinking systems that are beneficial to everyone.”

“Homosexual activity should be limited to kissing and hugging”

The most unenviable part of this new system had to be testing video games for the Infocomm Media Development Authority (which replaced the MDA in 2016) and writing up the elaborate explanations for how video games received their ratings:

The player may encounter an implied scene of fellatio between a male character and a non-human, talking towel character, but the act is obscured by a trash bin. The game also contains anime-style images of male characters in suggestive poses and acts of intimacy such as hugging and kissing.

These depictions can be allowed under the M18 guidelines, which permit “Portrayal of sexual activity with some nudity, both topless and frontal, if not detailed”, and state that “Homosexual activity should be limited to kissing and hugging.” (IMDA classification information for South Park: The Fractured But Whole)

While the rating system allows for the circulation in Singapore of games which might previously have been banned (previously banned games were now available under a M18 Rating), it has also drawn criticism.

Games that feature LGBT characters often receive higher ratings because of their LGBT content. An overview of the regulation of LGBT representation in the media by Heckin Unicorn notes that:

“Games that contain “homosexual themes” will be given an M18 rating if it’s discreet, or refused classification if not (page 4, para 15a; page 6, para 17dii). If the game features same-sex couples who hug or kiss, they automatically qualify for an M18 rating (page 5, para 15c).”

In effect, the rating system as it stands can limit the ability of LGBT youth to see representations of themselves in the games that they play. These representations can be an important avenue for LGBT youth to build self-esteem and mediate negative experiences relating to sexual orientation. A study on LGBT media representations argues that positive media representations are an important form of escapism and self-empowerment, and foster a sense of community among LGBT youth.

Is Singapore stepping away from video game ratings and controls?

Singapore was among the first countries in Asia (alongside Taiwan and South Korea) to introduce its own video game rating system and was the first in Southeast Asia to do so.

However, the actual strictness with which Singapore’s ratings and cuts are enforced today can be arbitrary, due to ambiguities in the classification system on when violence or LGBT content becomes so excessive as to require a higher age rating, cuts or to be refused classification entirely.

Games that prominently treat same-sex relationships on equal footing with opposite-sex ones, such as The Sims or Hades, received a Suitable for 16 and Above Rating. This could indicate that LGBT content might not factor into the rating if the straight tester never discovers it — or if the presence of such content is seen by the IMDA as uncontroversial to the public.

To take another example, South Park: The Stick of Truth was released in Singapore as a low-violence version with cuts. However, a game which was arguably as explicit (if not moreso), Cyberpunk 2077, was recently released without cuts or a detailed explanation behind its M18 rating. One can only imagine how the IMDA would even begin to describe the content it might deem questionable in a game that features customisable genitals.

With some recent games not even receiving a detailed explanation for their rating (past games received in-depth classification information), it is unclear what the future of these advisories and the rating system as a whole will be.

Video Game Censorship Today

While Singapore's early history of video game censorship was fuelled by the moral panic over the danger posed by video games, the censorship of popular games was often ineffective. Many bans were short-lived because of public backlash, and video gamers' persistent desire to play these games created workarounds like Singapore's early internet cafes.

Over time, as Singapore sought to position itself as a hub for digital media development in Asia, a draconian video game censorship regime did not only make for bad press — it was also bad for business. Being the country known for banning a game for "lesbian intimacy" did not mesh well with Singapore's ambitions for its growing video game industry.

As a sign of how video game censorship might have taken a more subtle turn in recent times, one need only look at the case of Witching Hour Studios' fantasy RPG Masquerada. In 2015, Gamasutra broke the story of how this Singapore-based studio risked government censorship to release their game.

According to Gamasutra, after the Studio revealed that one of the game’s main characters would be gay, civil servants in the Singaporean government approached the studio at industry events to suggest that the character be removed. This incident raises questions of whether informal and less visible channels are being used by the state when dealing with video game content it deems inappropriate.

After the introduction of the age-based rating system, outright bans on video games had become rare in Singapore. The most recent video game that was refused classification by the IMDA was a niche and sex-themed shoot-em-up game, Waifu Uncovered, for featuring excessive nudity.

Edit: Another recently banned game is Tell Me Why, which made waves for being the first major video game to feature a transgender protagonist. Users in Singapore attempting to purchase this game on the Steam store receive an error message. The IMDA has not released a statement explaining why the game has been barred from release in Singapore.

It is worth noting however, that such a ban is no longer as restrictive as it used to be. By 2021, how Singaporeans buy and consume their video games has changed significantly. Singapore's largest physical video game retailer closed in 2018. More recently, the pandemic has not only driven consumption online, it also likely contributed to the decline in LAN shops. Online, the impact of restrictions (like low-violence versions or region locking) are likely to be less impactful, simply because of the variety of workarounds available to users.

Perhaps this increasingly limited impact of video game restrictions is why many of the IMDA's rating explanations for games which might once have been refused classification are now simply left blank.

For more stories on Singapore's internet, press and government, subscribe to receive email updates with each new issue's release.