POFMA: How is Singapore using its anti fake news law?

Who and what is targeted by Singapore's law against fake news?

Singapore's Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) has drawn significant controversy since its introduction in October 2019. How has the law been used? And what are its likely impacts on online misinformation and freedom of expression in Singapore?

This article uses the data I gathered for the POFMA’ed Dataset (see the methodology here) and some of the key insights from my article for the International Journal of Communication on how civil society in Singapore is affected by POFMA. By breaking down the 96 instances of POFMA’s use in terms of who it targets, what content it targets, and on what platforms, this article evaluates how Singapore is using its anti fake news law.

How does the POFMA'ed Dataset count uses of POFMA?

The dataset distinguishes between Reports, POFMA Uses and Communications.

Report. Each Report of POFMA legislation’s usage released by the government (via a POFMA Office Press Release) is given a Report number. Note that a Report can describe multiple POFMA uses, affecting different electronic communications.

POFMA Use. Each use of POFMA legislation (a direction or order) is given a POFMA Use number. Note that a single POFMA direction or order can apply to multiple communications.

Communication. Each distinct electronic communication which has been subject to a use of POFMA legislation is given a Communication number. Note that a single electronic communication can be subject to multiple uses of POFMA legislation.

These distinctions are necessary because of how a single Report can describe multiple uses of the POFMA legislation, each of which could affect multiple distinct electronic Communications.

For example:

According to Report 1, a Facebook post is the subject of a Correction Direction, issued to Individual A and requiring them to amend this post.

According to Report 2, this same Facebook post is also the subject of a Targeted Correction Direction, issued to Facebook and requiring them to amend this post, due to Individual A's non-compliance with their Correction Direction.

This dataset would thus track that Facebook post as one Communication, subject to two distinct POFMA uses, according to two distinct Reports.

Explainer: What even is POFMA?

POFMA was introduced in October 2019 as Singapore’s legislative response to online misinformation. The law can be used to (among other things) require someone to post a correction notice for a statement they have made, or to require platforms or service providers to block access to specific pieces of content. A prerequisite for all uses of POFMA is that it is in the public interest, and that it targets falsehoods.

However, POFMA defines both of these terms very broadly. Public interest includes (but is not limited to) public confidence in government and friendly relations with other countries. POFMA has also drawn controversy for how it defines falsehoods and its impact on freedom of expression in Singapore.

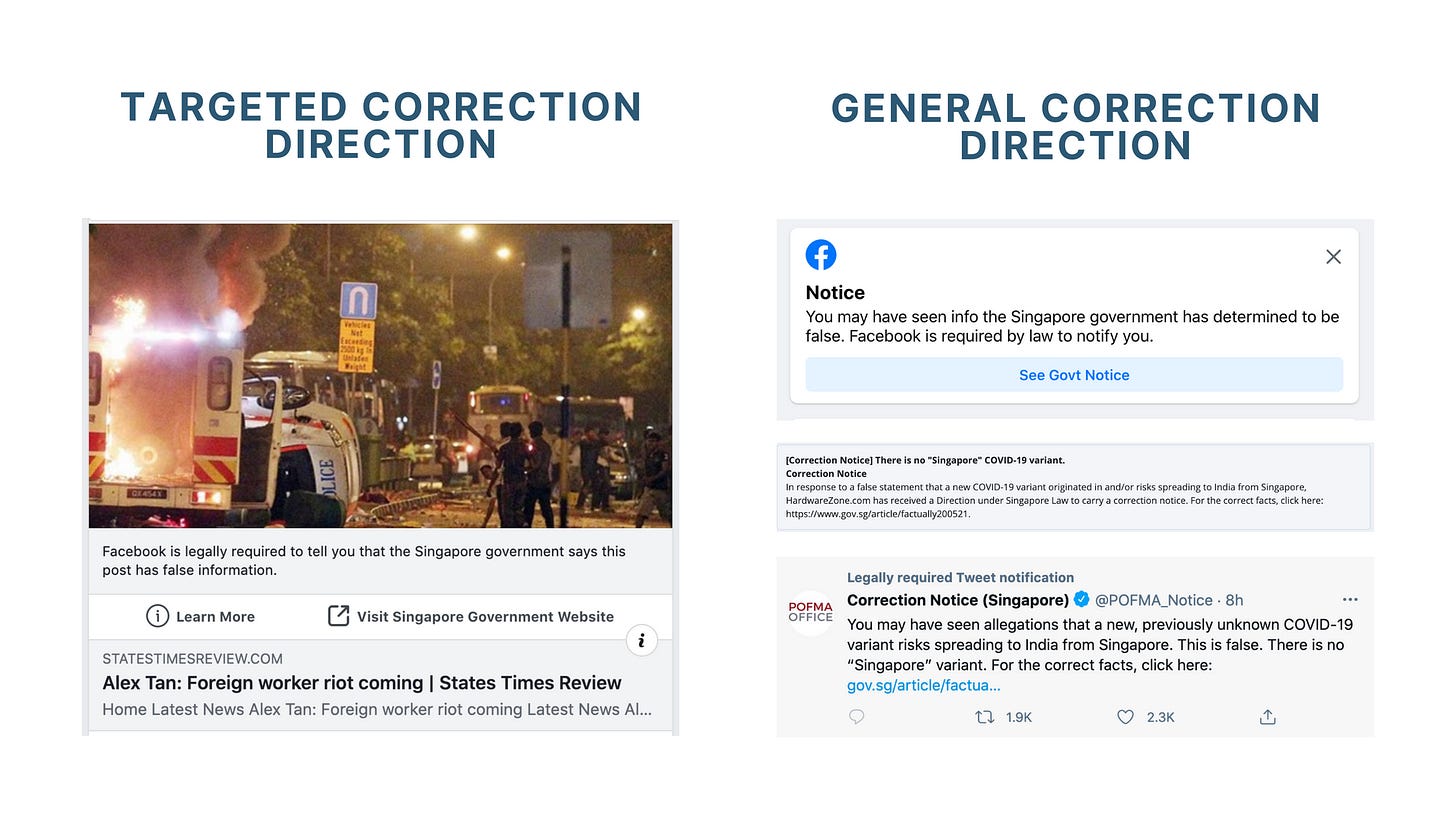

The vast majority of times POFMA has been invoked, it was used to issue correction directions, which require users or platforms to include a notice indicating that a specific post or article contains a false statement of fact. Non-compliance is an offence, and on conviction, one is liable to a fine or imprisonment.

Only a small minority of POFMA’s uses go beyond the labelling of content as misinformation: Malaysian organisation Lawyers for Liberty had their website blocked under POFMA after accusing Singapore of conducting its executions in a brutal manner. Alex Tan, an Australia-based dissident, has had multiple Facebook pages (including the States Times Review) blocked under POFMA.

Any minister can instruct the POFMA Office to issue a direction or order under POFMA if the above conditions of falsehood and public interest are met. However, the procedure by which falsehoods are discovered is unclear, and there is ambiguity over who exactly is responsible for detecting misinformation in Singapore's media landscape to the ministers. According to the Singapore government directory, the POFMA Office has only 10 listed employees, of which only 5 work under "directions, compliance & investigations."

POFMA in numbers: Who gets POFMA'ed?

The actors most frequently subject to correction directions are opposition groups or figures, such as the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP) or Lim Tean, leader of the opposition party, People’s Voice. One figure, Alex Tan, the controversial figure behind the States Times Review, accounts for 18 of these POFMA uses — the most of any target actor.

Media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and SPH (who run the HardwareZone Forum) have also been subject to POFMA. These platforms can receive "targeted" or "general" correction directions. Targeted correction directions require them to include a correction notice over specific statements made on their platforms.

Meanwhile, general correction directions require these platforms to share a correction notice more broadly, sometimes towards all their users in Singapore.

Other than Australia-based Alex Tan, and the Malaysia-based groups New Naratif and Lawyers for Liberty, there have been no known instances of other foreign actors being subject to POFMA. This is despite some of the high-profile falsehoods identified by the Singapore government originating abroad.

A Taiwanese talk show made allegations about Ho Ching's salary before POFMA's use against local politician Lim Tean and independent news website The Online Citizen for making similar allegations. An Indian politician was the first to spread the idea that a new COVID variant had been discovered in Singapore, but POFMA was used on Facebook, Twitter and the HardwareZone Forum to require these platforms to display a notice to all users in Singapore, while the politician himself was not targeted.

What gets POFMA'ed?

Half of all POFMA uses (48 out of 96) have been directed at content relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. A notable example of this is the use of POFMA against Truth Warriors, a website spreading anti-vaccine misinformation.

Nearly all POFMA uses are directed at statements which relate to government institutions or officials (e.g. ministers and ministries, schools, prisons), government policies (e.g. the budget, population policies, POFMA), or the government’s handling of COVID.

There are a few exceptions to this, including: allegations about the salary of Ho Ching (CEO of Temasek and wife of the Prime Minister); allegations that a new COVID variant had been discovered in Singapore; allegations that Singapore was running out of its supply of surgical masks; allegations that the COVID vaccine is ineffective and that ivermectin should be used against COVID; and allegations about the Omicron variant being a combination of HIV and COVID.

Even though large sections of the law specifically target online inauthentic behaviour, such as bots or phishing, there are no reported instances of POFMA being used to target online scams or online mass manipulation through bots. Instead, such misinformation seems to fall under the purview of the ministries’ communication teams or local media:

In the fight against fake news, Facebook is the main battleground

The vast majority of POFMA uses have been directed at content shared on Facebook, which accounts for 66 out of the 99 total communications subject to POFMA.

This pattern potentially highlights a key flaw in POFMA. Its statement-specific and legalistic approach to misinformation does not address forms of misinformation which are beyond the state's notice or which are inherently harder to track — such as conspiracy theories, foreign influence operations, and xenophobic rumours which spread through more dispersed platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram.

Which minister has used POFMA the most?

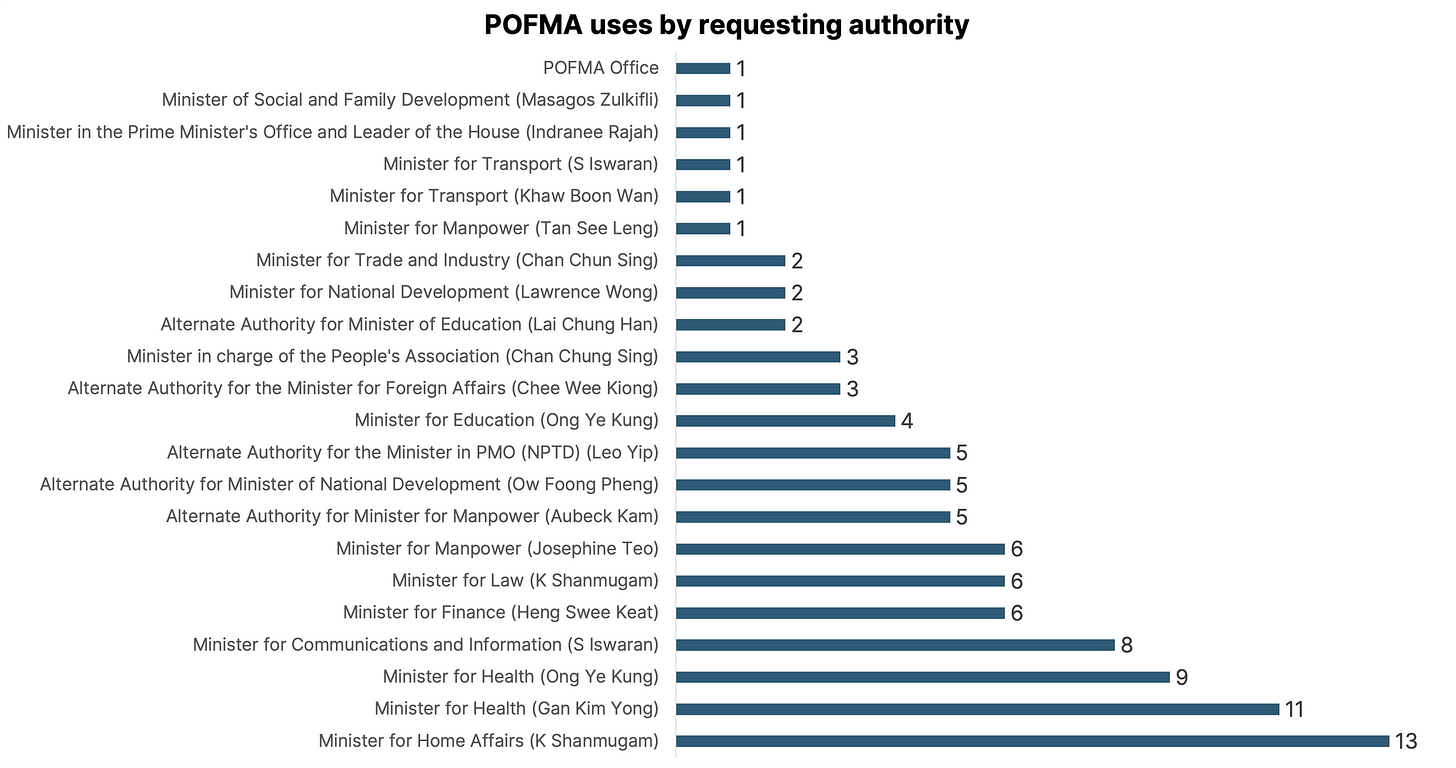

Each use of POFMA has been requested by a minister or an alternate authority (appointed during election periods), with one exception. Ministers usually target statements which fall within the domain of their work. For example, the Minister of Health has invoked POFMA against health misinformation such as allegations that COVID vaccines are ineffective at reducing COVID transmission.

It should come as no surprise that the most ardent advocate for POFMA is also its most prolific user. Minister for Law and Home Affairs K Shanmugam has requested at least 19 POFMA uses, the most of any minister. However, the Ministry of Health, previously helmed by Gan Kim Yong, and currently led by Ong Ye Kung, is responsible for the most POFMA uses overall (20).

Only three ministries have never made use of POFMA: Defence (MinDef); Culture, Community & Youth (MCCY); and Sustainability and the Environment (MSE).

Is POFMA’s use declining in favour of other tools?

The period which saw the greatest number of POFMA uses was the General Election 2020. The month of the election (July 2020) saw 27 POFMA uses, the most of any month since the POFMA's introduction. Following this, and until April 2021, there was an 8-month gap in which there were no reported uses of POFMA.

Notably, POFMA's usage has been declining over time. In 2020, POFMA was used an average of 9.14 times a month, while in 2022 (so far), POFMA has been used an average of 1.5 times per month.

Is POFMA an effective tool for countering misinformation?

Sometimes, the usage of POFMA can be counter-productive to the intended goal of curbing the spread of misinformation. Nearly every use of POFMA is coupled with reports from local media, outlining what falsehoods have been subject to the law, and potentially bringing it to the attention of many who might otherwise never have seen it.

Some uses of POFMA have also drawn international attention and scrutiny, putting the statements it targets under a global spotlight:

Perhaps the best example of this counterproductive effect is when it was used against social media posts speculating about the salary of the Prime Minister's wife, Ho Ching. This use of POFMA drew intense coverage from international media, and outcry from Singapore netizens. Indeed, Google search interest in the term "Ho Ching's Salary" spiked in the period when POFMA was used (19-25 April). A similar trend can also be seen for search interest in the term “truth warriors” after POFMA was used against the Truth Warriors website, which promotes anti-vaccine misinformation.

Here, we can see POFMA falling prey to what is known as the "Streisand Effect", where attempts to counter the spread of a specific piece of content instead make it more viral.

However, this is not always the case. I previously highlighted how POFMA's lightning rod, Alex Tan, has created a new Facebook page whenever one is banned. Each subsequent Facebook page has seen a significant decrease in the number of followers, showing that when POFMA shows its teeth, its targets do feel the crunch.

The Lawyers for Liberty website is also no longer accessible in Singapore due to POFMA. While search interest in "lawyers for liberty" in Singapore spiked in the immediate aftermath of the POFMA order, search interest for the organisation in Singapore has flattened to nothing in the long-term, despite the organisation's ongoing involvement in lobbying the Singaporean and Malaysian governments over high-profile death penalty cases.

Overall, for those spreading allegations about a cover-up from the state or conspiracy theories (with low trust in the state and official sources), more research is necessary to understand whether POFMA persuades these readers or hardens their distrust. Research about vaccine hesitancy among the elderly points to trust in formal information sources correlating with vaccination status. Whether POFMA helps to persuade those who are already sceptical towards official sources remains an open question.

POFMA and its impact on political discourse

POFMA is part of a broader trend of states introducing new legislation to tackle the problem of misinformation. In this larger trend, there is growing concern over how these new laws might influence political discourse, and whether they might constitute new forms of censorship.

As part of an academic journal article on POFMA, I conducted a qualitative and interview-driven study with 17 Singapore-based academics, journalists, and activists on their experiences with POFMA and other laws governing speech in Singapore. Two key themes emerge across most interviewees:

The first is that POFMA allows the state to create highly visible rebuttals. However, in doing so, POFMA also potentially creates new openings for highly visible backlash and resistance, triggering further discussion and debate due to the spotlight it casts on a specific statement.

The appeals process for POFMA is illustrative of this. Although most POFMA uses go uncontested, a few have been challenged in court — which then become subject to intense media scrutiny, both locally and internationally. Most notably, the SDP succeeded in having part of the POFMA direction against them overturned, only to be slapped with another new POFMA direction. SDP's statement about their plans to appeal against this highlights how POFMA can contribute to and prolong the media cycle and social media discussion of these "falsehoods", rather than the opposite.

Secondly and perhaps more importantly, POFMA has a more subtle impact in that it raises the bar of evidence necessary for statements about politics in Singapore, without necessarily making more evidence or data available for discussion. Ambiguities and uncertainties around both POFMA and other laws governing speech can lead to greater self-censorship. It can also motivate some users to move away from more public platforms like Facebook to spaces less subject to surveillance or scrutiny.

Again, the appeals process for POFMA is revealing. After conflicting views between different judges, Singapore’s High Court has ruled that the burden of proof lies with the recipient of a correction direction when seeking to make a legal challenge. Without access to data or information necessary to confirm or substantiate allegations which become subject to POFMA, this functionally means that a vast swathe of issues on which comprehensive and publicly available data does not exist are beyond the realm of contentious online discussion.

The future of POFMA

POFMA is only one part of Singapore’s "whole-of-society" approach to countering misinformation. Other tools include the use of media literacy campaigns, such as the National Library Board’s SURE, or the use of government communications and local media to highlight misinformation and inauthentic behaviour.

However, POFMA’s declining usage points to ambiguities over POFMA’s current purpose. Its pattern of use suggests that other tools are becoming more important in the Singapore government’s approach to misinformation — or at least, for misinformation which goes beyond that which undermines trust in public institutions.

It is too early to conclude that POFMA will continue "declining" in usage, because you did not consider cyclical trends.

As noted in your article, POFMA usage by ministers peaked during the General Elections 2020 period, wielded as a tool against opposition and dissident voices who pointed out harsh truths about policy failures.

It then decreased afterwards for the next 4 years because its primary purpose (to silence opposition voices so as not to lose votes) did not exist for those 4 years.

With the upcoming General Elections of 2025, the usage of POFMA will rise once more, and this article will be in need of an update.