Singapore is known for its tough and pro-death penalty stance on drugs, to the point of drawing international condemnation for seeking to execute a man with an intellectual disability for smuggling drugs. On the face of it, such an approach seems like it would be effective in curbing drug addiction and trafficking, but much of the evidence shows otherwise.

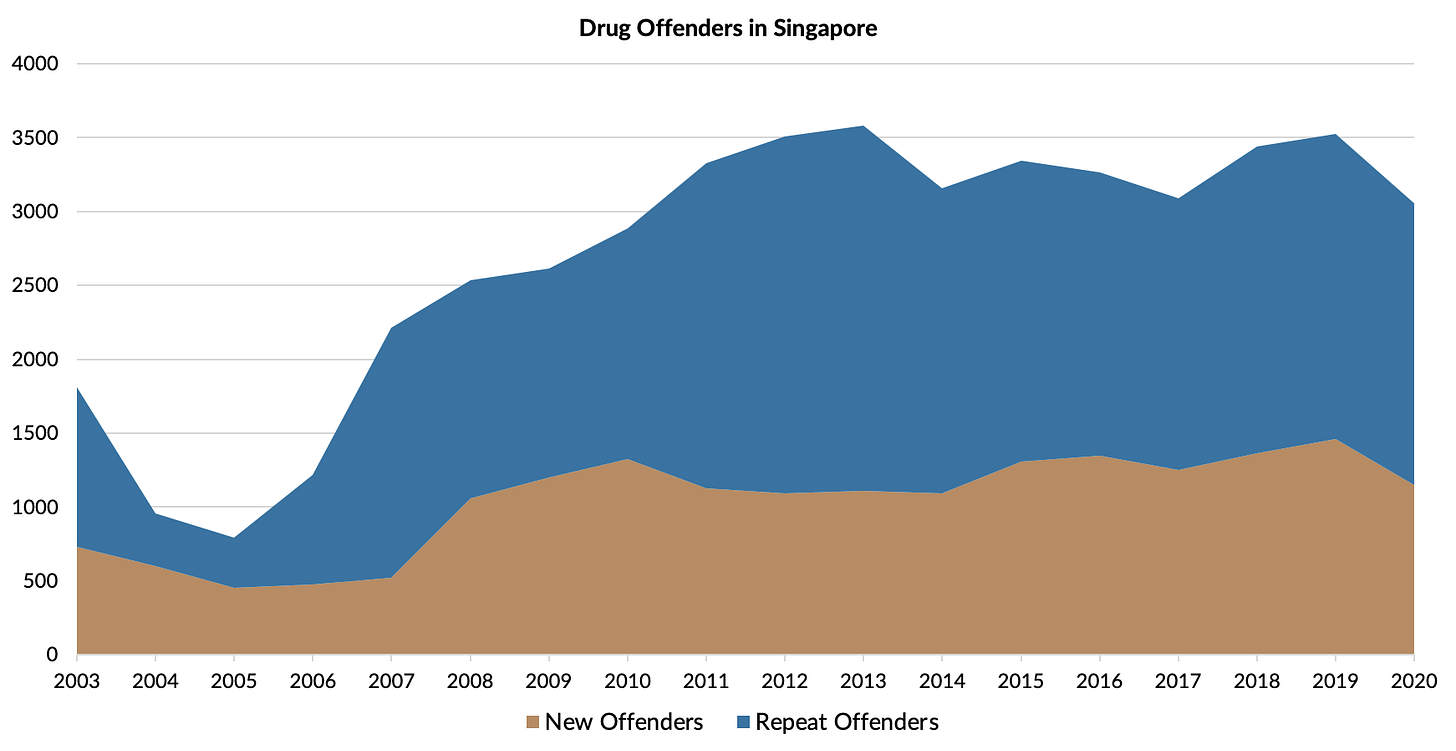

According to the Singapore Prison Service, those convicted of drug offences made up around 67% of Singapore’s prison population in 2020. When compared to other contexts, this is a disproportionately high figure. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, around 19% of male prisoners and 35% of female prisoners are imprisoned for drug offences worldwide. Moreover, the issue of drug abuse has been a persistent one in Singapore, with a stable number of both new and repeat offenders over the past decade.

What explains the contradictions between Singapore's drug policy and its actual outcomes? This issue of Singapore Samizdat explores Singapore's war on drugs, and the censorship and social costs behind it.

Singapore's anti-drug policies are nightmarish for the underprivileged, negligible to the rich

While Singapore actively dehumanises drug users and justifies punitive measures against them, the actual impact of its drug policies differs greatly between groups.

Many of Singapore's drug policies have a horrifying potential for cruelty. Singapore’s Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act allows the authorities to detain an individual indefinitely without trial, if they are suspected of drug trafficking. Singapore's Misuse of Drugs Act makes it an offence to not only traffic drugs, but also to provide information on drug use (even online). The authorities can also demand a urine test without a warrant, with refusal seen as a sign of guilt.

In response to recent allegations that cruel treatment from the Central Narcotics Bureau led to the suicide of a Singaporean teen, the authorities' internal probe found no wrongdoing, despite an impassioned plea from the teen's mother. But cases like these are not one-offs. The Transformative Justice Collective has shared stories from those who have experienced this dehumanising and cruel treatment, which are far from rehabilitative.

But the worst by far is reserved for those who are caught up in drug trafficking. Numerous reports and investigations have shown that drug mules (those who carry drugs for international drug rings) often do so under duress and coercion, or because of deception or desperation. Some do so unwittingly, becoming victims simply by grabbing the wrong piece of luggage.

Singapore's drug laws presume drug possession even in cases where there is no evidence that one has come into physical contact with the drug, and requires the death sentence for possession past a certain amount. Many have argued that such harsh laws only catch those on the lowest rungs of organised crime, and does little to dissuade bosses and kingpins, who can avoid drug possession while profiting from such crime.

Racial and sexual minorities

How do Singapore's drug policies impact racial and sexual minorities? While Singapore's resident population is more than 70% Chinese, racial minorities are disproportionately represented among drug offenders:

A lawsuit was recently filed on behalf of 17 Malay death row inmates accusing the government of racial bias (though it was dismissed in early December). Singapore has even been questioned on the disproportionate impact of its use of the death sentence by the United Nations' Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination:

In the context of Singapore, there was a minority ethnic problem. Malay made up 13 per cent of the population, yet figures showed that they made up 84 per cent of executions for drug trafficking. That was a gross disproportionality. There had to be a reason to explain that difference.

Prior testimonies also suggest that sexual minorities receive different treatment from drug enforcement authorities. A story for the Transformative Justice Collective writes:

The other inmates offered him tips, pointing out to him the “homosexual cell” that was visible through the little sliver on their cell door. According to them, those who declare themselves to be homosexual are incarcerated in DRC for 12 months with no chance of release, while others have the chance to access programmes after 4 to 6 months.

As I write this issue, I cannot help but recall my experience of being taken in by the Singapore Armed Forces' military police for drug testing, and being told that the reason I was to be tested was because someone in my unit had informed them that I am gay. As part of my interview, I was asked probing and disturbing questions about my sexuality. Even after a negative drug test, the military police grilled me for the names of all the gay men I knew in the military, for reasons that I can only speculate on.

But for the wealthy and privileged...

For those able to afford discreet treatment and trips to partake in vice, Singapore's drug policies have an unequal impact. Recreational drug tourism (visiting other countries to consume drugs which are illegal in your own jurisdiction) is a growing industry. Non-legal consumption is also a driver of tourism to a number of destinations — such as Bangkok, Prague, Berlin, and Bogota — a concept that is far from alien to Singaporeans. Further, much less attention is dedicated by the government to the abuse of prescription drugs for recreational purposes, an issue more likely to be prevalent among the haves than the have-nots.

In cases of addiction, the rich can turn to international rehabilitation centre chains such as The Cabin, which offers “the strictest standards of confidentiality” and treatment at an inpatient rehab centre in Chiang Mai, Thailand. This “luxury facility is worlds away from all addiction triggers making it an ideal setting to begin the healing process.” Contrast this to government-run rehabilitation centers and the gap between the rich and the poor in accessing treatment becomes stark.

Noteworthy cases of charges being brought against members of the privileged upper class include the trials of high society figures such as Dinesh Bhatia or Ong Jenn. The former was even represented in court by the current Minister of Law and Home Affairs Shanmugam himself, who reportedly argued that Bhatia did not realise the substance he was snorting was cocaine. He was given an eight-month prison sentence, part of which was reportedly served from home.

In an age of increasing global liberalisation and scientific support towards the legalisation of drugs such as cannabis, Singapore's restrictive policies essentially create one set of rules for transnational elites and another for those who are Singapore-bound.

Singapore is killing rational discourse on drug abuse and trafficking

A little-known fact about censorship on Netflix is that most government-requested takedowns of Netflix’s content come from Singapore. According to Netflix, 7 out of the 13 programs removed from a country's platform were requested by Singapore — making Singapore Netflix’s “most censored market”. Nearly all of them contain depictions of drug or alcohol use. For a small city-state, Singapore certainly punches above its weight in censorship.

Potential reasons for this overzealous censorship include the Misuse of Drugs Act, or Singapore’s content standards, which prohibit programmes that “promote drug or psychoactive substance abuse, or includes detailed and instructive depictions of drug or psychoactive substance abuse.” This broad and often-arbitrary policing of narratives relating to drug use is not restricted to Netflix, and extends across media platforms in Singapore.

Under this policy, the state restricts the kinds of narratives surrounding drug use that Singaporeans can see — a symptom of Singapore's lacking nuance in issues of addiction and recreational drug use — while pushing its own narratives.

High.sg: how Singapore exploits narratives to justify execution and incarceration

One need only look at Singapore’s first interactive film to see this in action. High.sg is an interactive film much like Netflix’s Bandersnatch. Funded by the National Council Against Drug Abuse, this interactive experience presents a cliched story that Singaporeans should know all too well. A chaste and Chinese everyman protagonist is lured into a world of drugs and addiction by a seductive woman and her stereotypical gangster clique, turning his life upside down.

Like much of the material used in drug education in Singapore, the story claims to show "the two sides of drugs," the horrifying truth of drug abuse that drug dealers do not want you to know. In actuality, High is an overly simplistic tale that associates drug use with smoke-filled rooms, strobe lights, party girls, good sex, and walking racial/gender stereotypes. Explorations of the underlying social issues and complex motivations which contribute to drug use are peripheral to the idea that drug use is solely a selfish and irrational choice, a point which the story repeatedly hammers into the viewer by allowing them to make choices at key points in the story.

By painting drug users as irrational deviants in need of state control and guidance, state-sponsored narratives like High justify harsh punishment and mass incarceration, without addressing the social inequalities and issues which allow drug abuse to propagate itself in society. The lacking nuance in such stories is made all the more troubling when one considers the intensity with which the state pushes such campaigns on the public, and censors or delegitimises views that it disagrees with.

With narratives such as these, is it any wonder that public opinion backs cruel and punitive measures against drug users and traffickers?

That is not to say that exceptions to the norm do not exist. Singapore students of a certain age might remember reading Alfian Sa'at's short story, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Hanging, for their secondary school literature classes. Thirteen Ways is a thought-provoking and grim fictional depiction of a man sentenced to hang for drug possession. Sadly, stories such as these are few and far between in the mainstream.

The result: say no to drugs, on steroids:

Both domestically and internationally, Singapore pushes the idea that there is no difference between “soft” and "hard" drugs. Soft drugs are commonly understood to be less hazardous, and thus usually require less strict controls and punishment. For example, many states consider cannabis (marijuana) to be a “soft” drug.

Singapore refuses to recognise any such distinction, and instead peddles overly simplistic education materials — which include flawed statements like cannabis (which is legal in many jurisdictions, for either recreational or medical purposes) being just as bad as heroin.

Placing all drugs in the same category allows government officials to more easily create misleading straw man arguments against those campaigning for an end to the death sentence, by accusing such groups of seeking to legalise a number of harmful substances.

Ultimately, such narratives are harmful, partially because they often do not work (studies in other contexts indicate that similar drug education programmes can have no effect) and partially because they are misleading. Individuals exposed to drug use who come to realise that the state's discourse is out of touch with reality are less likely to trust the state in the future.

Singapore's harsh stance on drugs is not evidence-based

When pressed to defend Singapore's death penalty, the Singapore government has cited reasons such as the reduction in opium (a drug that has become increasingly obsolete and unpopular globally) trafficking in Singapore and a 15-19% reduction in the likelihood that one would traffic a volume of cannabis that would warrant the death sentence (500 grams). The state has also argued that there is strong public support for the death penalty — without acknowledging that popularity does not constitute scientific consensus or evidence.

Singapore has also argued in favour of its zero-tolerance strategy, in opposition to harm reduction policies gaining ground elsewhere in the world (most notably in Portugal, the Netherlands and Switzerland). Minister Shanmugam has even argued against the United Nations' reclassification of cannabis as a less harmful drug. The Minister has claimed that profit motives are behind the scientific evidence for the use of cannabis for medical purposes, and that Southeast Asia is the second-largest market for methamphetamine (which the UN decision does not affect).

What is harm reduction? Harm reduction is an approach to drug policy grounded in human rights. It aims to reduce the negative impacts of drug use by focusing "on positive change and on working with people without judgement, coercion, discrimination, or requiring that they stop using drugs as a precondition of support." Key principles include a commitment to evidence, a commitment to social justice, respecting the rights of drug users, and the avoidance of stigma.

The actual scientific evidence for the effectiveness of the death penalty and mass incarceration for deterring drug-related offences is limited and often contradictory:

Many studies have found that there is no link between imprisonment for drug offences and a reduction in drug-related crimes.

Indeed, studies also point out that evidence for the deterrent effect of the death sentence is inconclusive. Some have argued that death sentences brutalise society, undermining the value of human life and potentially having the counter-productive effect of causing more murders.

Many studies also explain that addiction should not be seen as a crime, but instead as a health issue to be treated. These studies call for states to adopt a harm reduction / public health approach to drug abuse.

Crucially, while there remain ambiguities behind key questions in drug enforcement, there is little credible evidence supporting the use of the death penalty, or the use of mass incarceration over treatment.

Why drugs are not like cigarettes or alcohol, or what evidence-based policy looks like

In contrast to Singapore's approach to drug policy, one can look at another set of policies driven by research on human behaviour and economics: Singapore's approach to restricting cigarettes and alcohol.

Rather than outright banning cigarettes or alcohol, Singapore uses a variety of subtle measures to disincentivise smoking and alcohol consumption, like raising prices through taxes or restricting when/where cigarettes and alcohol can be consumed (fewer smoking corners, requiring alcohol permits to sell past a certain time). Consequently, Singapore ranks as the fourth most expensive city to buy a pint of beer out of 48 major cities, and as the eighth most expensive country in the world for buying cigarettes.

These techniques are effective, with Singapore's alcohol consumption among the lowest in the Asia-Pacific region, and with tobacco consumption reducing every year. Notably, the success of these policies speaks for itself, despite mixed public support — has anyone ever cheered for the rising price of alcohol? Crucially, while the demand for cigarettes and alcohol is very sensitive to differences in price and accessibility, the same cannot be said for drugs. Against intuition, research indicates that limiting supply or criminalising drugs does not always lower demand, and other strategies may be more effective.

Is harm reduction incompatible with Singapore?

An alternative to criminalisation and harsh punitive measures is harm reduction. However, Singapore has frequently argued that harm reduction does not work, pointing to its brief legalisation of subutex as a prime example. Subutex (also known as buprenorphine) is an opioid prescribed by doctors to treat addiction to opioids such as heroin. Hoping to tackle the use of heroin in Singapore, the state legalised subutex in 2002. By 2006, subutex was banned and made a controlled drug. The state has stated that this was because it had observed the emergence of a "needle culture", which saw drug users abuse subutex by mixing it with other substances.

However, some have argued that there were issues with Singapore's legalisation of subutex, such as a lack of training and preparation for doctors who prior to this rarely dealt with drug abuse, or the evidence for how suboxone (a mixture of buprenorphine and naloxone) would be a better option due to its far lower potential for abuse.

Additionally, research from other contexts where subutex is available show that there are medical benefits even for illicit subutex use, as those using it generally seek to wean themselves off of dependence to worse opioids. This is especially relevant for those who cannot or will not access substance abuse treatment, when they try to escape the revolving door of opioid abuse.

Although the Singapore government considers its brief legalisation of subutex as evidence for the failure of harm reduction measures, one can also see how the state's brief and ill-planned approach to subutex is what doomed harm reduction in Singapore.

Does harm reduction work? In 2001, Portugal took the radical step of decriminalising personal drug possession. Possession is no longer punishable with imprisonment, and those found in possession are instead referred to health and social services, freeing up the police to pursue more severe drug-related issues (such as trafficking). Currently, Portugal has among the lowest rates of drug consumption in Europe and has significantly reduced the negative social impacts of drugs. Experts have argued that it was not only the decriminalisation that made this possible, but also the state's support of harm reduction and expansion of treatment/support services.

An end to Singapore’s War on Drugs?

While there are small signs that Singapore’s harsh stance on drugs is changing, the broad direction of Singapore's drug policies remains unchanged. In 2012, Singapore amended its laws to create narrow exceptions to its mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking. In 2019, Singapore's laws were again amended, this time to allow for repeat offenders without other offences to undergo rehabilitation without incarceration, and to allow for some offenders to undergo rehabilitation without gaining a criminal record. However, during a recent speech, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, explicitly condemned harm reduction approaches and the global trend towards legalisation — rejecting reform and backing a continuation of current efforts.

Elsewhere, efforts to dehumanise drug users and traffickers, and to ruthlessly incarcerate or execute them have been widely acknowledged as unjust, cruel and ineffective. The world is entering a tipping point, with global perceptions of drug use becoming more nuanced, and movements to abolish the death penalty and mass incarceration gaining ground.

The path to the end of the war on drugs is paved with ruined lives. For Singapore to achieve a more compassionate, rehabilitative and evidence-based approach to drug policy, Singaporeans should not turn a blind eye to the suffering that today’s drug policy entails. Take action by adding your name to the petition to pardon Nagaenthran, by supporting the Transformative Justice Collective, or by volunteering your time as a Befriender or Volunteer with the Singapore Prison Service.