Why did Singapore's Largest Newspaper Restructure into Nonprofit Press?

Behind the Singapore Press Holdings restructuring: umbrage over government control of the media, COVID-19's investment burns and the powerful new alternatives to mainstream media.

In this issue: What are some of the potential reasons behind the recent restructuring of Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) into nonprofit media?

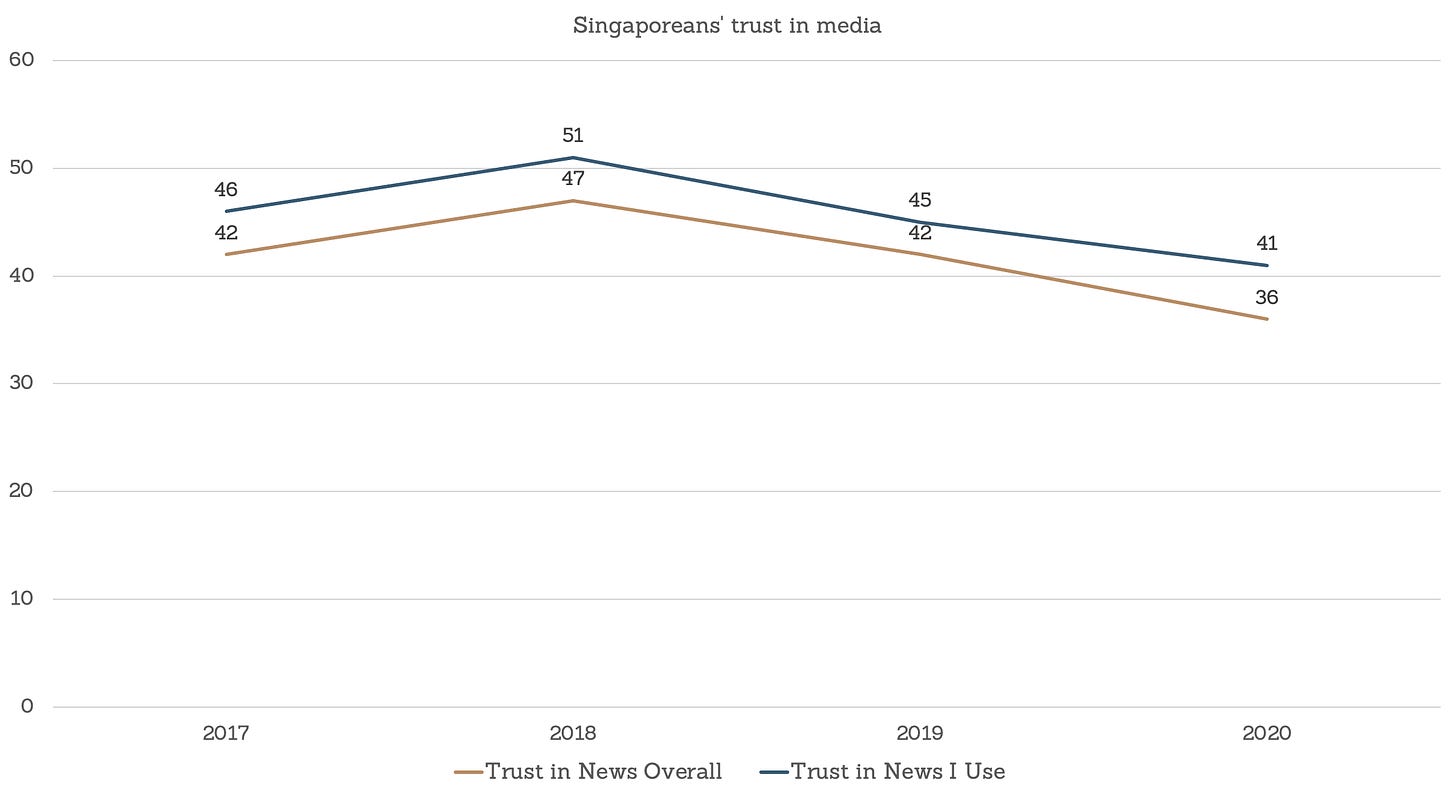

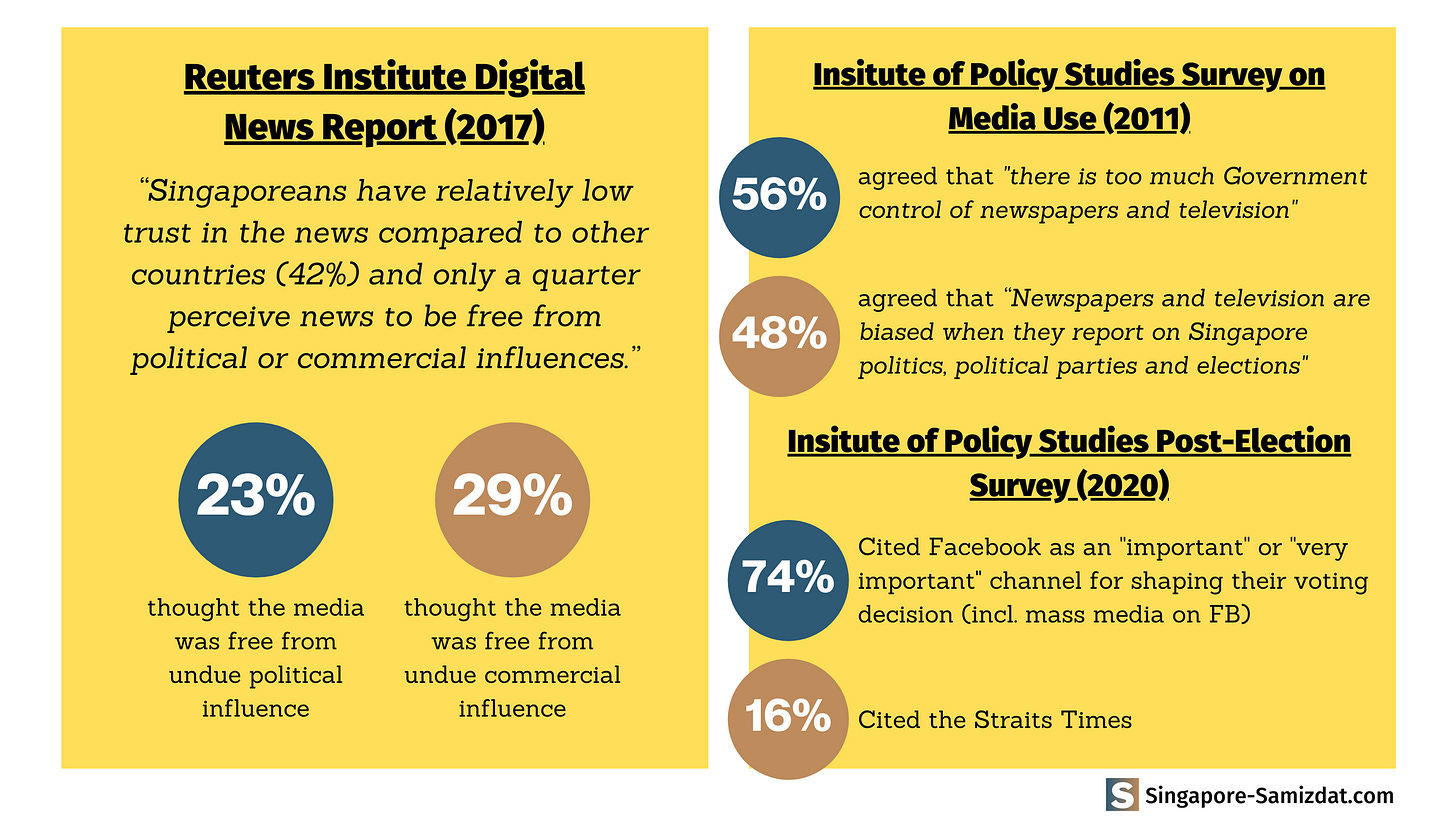

Do Singaporeans trust their media?

According to the Reuters Institute Digital News Report, less than half of Singaporeans trust the news in Singapore. This has stayed constant since the report began its surveys in 2017. In 2020, only 36% of respondents indicated that they trust the news in Singapore.

However, this report also places the Straits Times (SPH's largest newspaper) second for trustworthiness — while digital outlets such as All Singapore Stuff, The Online Citizen and Mothership rank last among top media brands. ST’s result means it performs significantly better than leading press outlets in other states:

With higher levels of trust from local consumers compared to other leading media outlets, what explains consumers’ lacking desire to support journalism from The Straits Times? A potential explanation for this lies in public perceptions of media bias and government control.

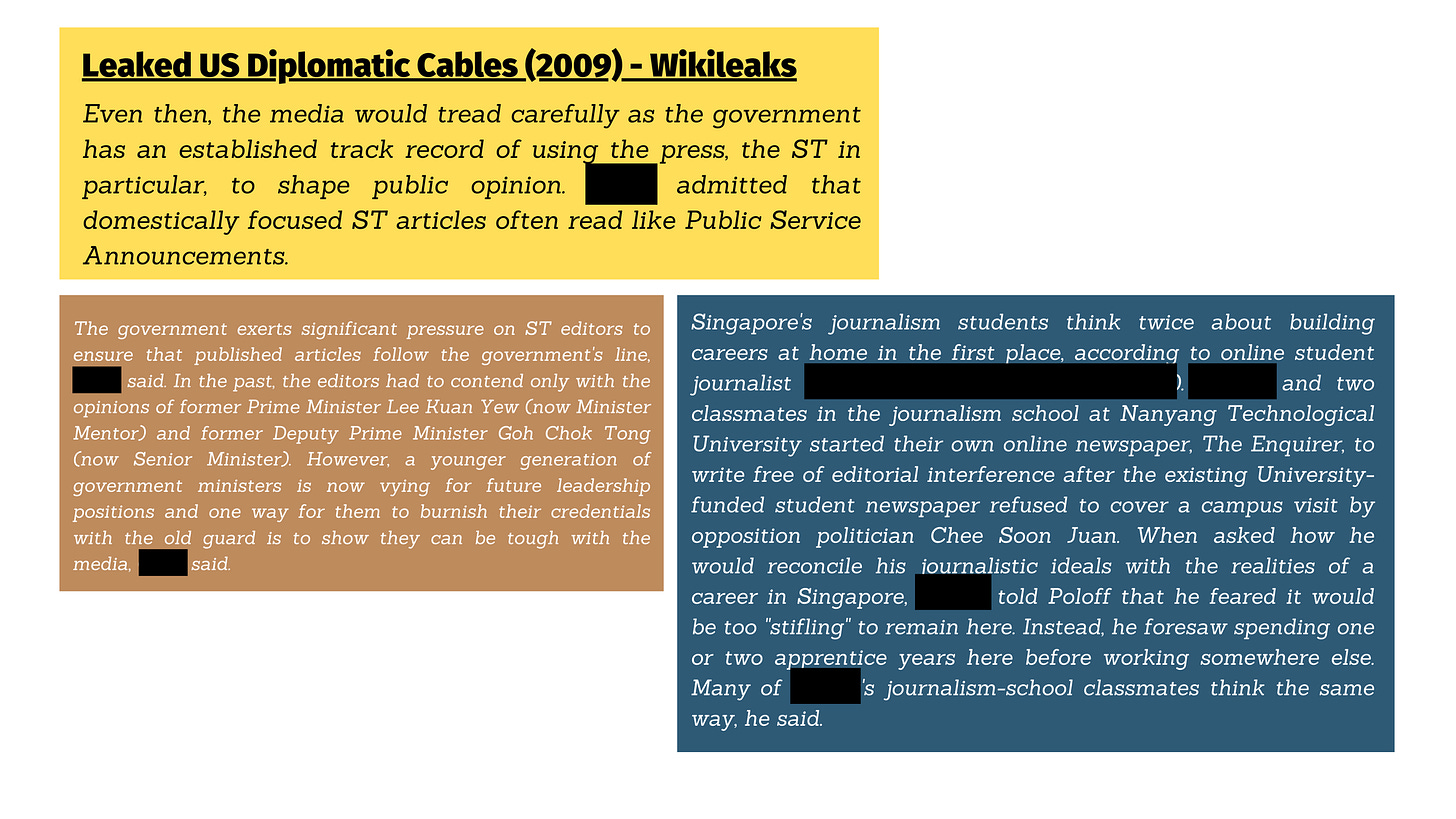

A more telling picture emerges from what journalists think of their own work: In 2011, US Diplomatic Cables leaked by Wikileaks offered a rare glimpse into how journalists in Singapore are “frustrated by press controls”:

Collectively, these indicators paint a picture of an SPH that is a reliable go-to source for Singaporeans on uncontroversial issues, but a poor one for contentious issues.

As some of the key reasons for why readers pay for their media include distinctive and high-quality content, as well as perceived benefits to society (from independent media that effectively holds politicians to account) — these indicators also imply that SPH would struggle to articulate a clear vision for why users should pay to support its safe and uncontroversial brand of local reporting.

These perceptions of bias are unlikely to change for SPH, not only because of the umbrage which occurred over the suggestion of lost editorial independence. Journalistic organisations that are known to be state funded (such as Voice of America or Al Jazeera) — and regardless of actual levels of editorial independence — continually struggle to escape accusations of bias towards their funders.

How press controls both help and hurt state-affiliated media

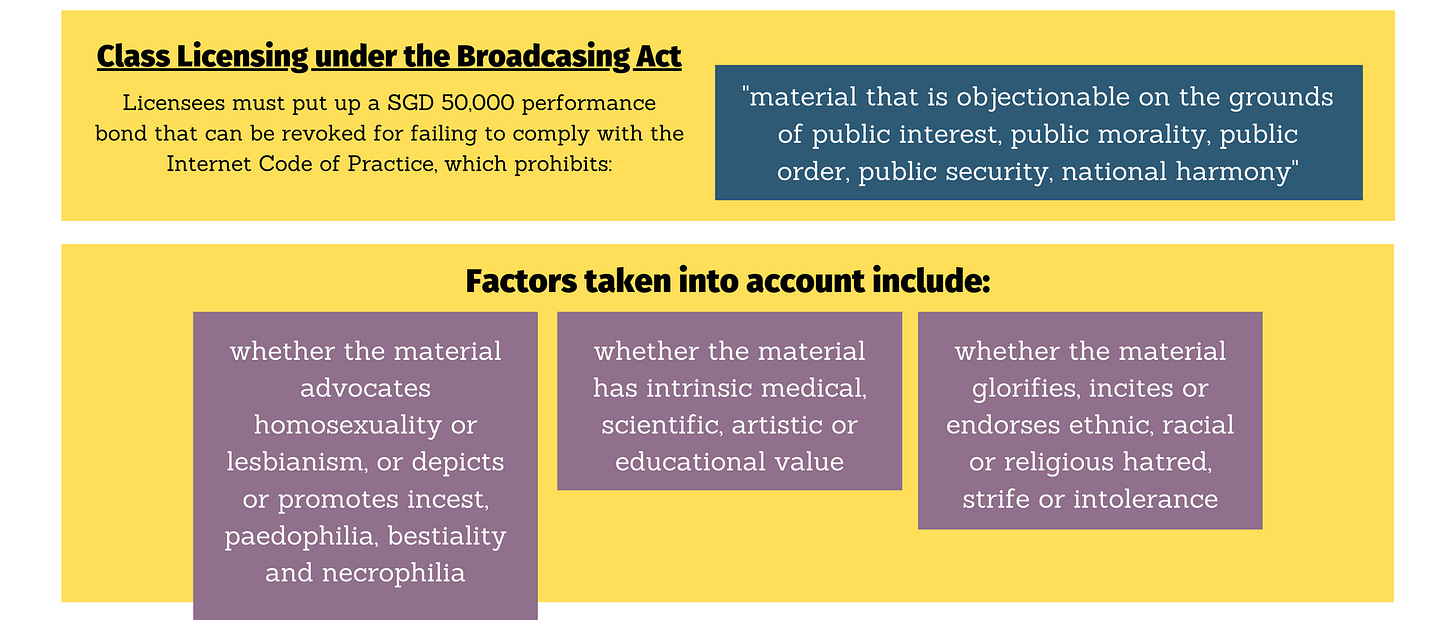

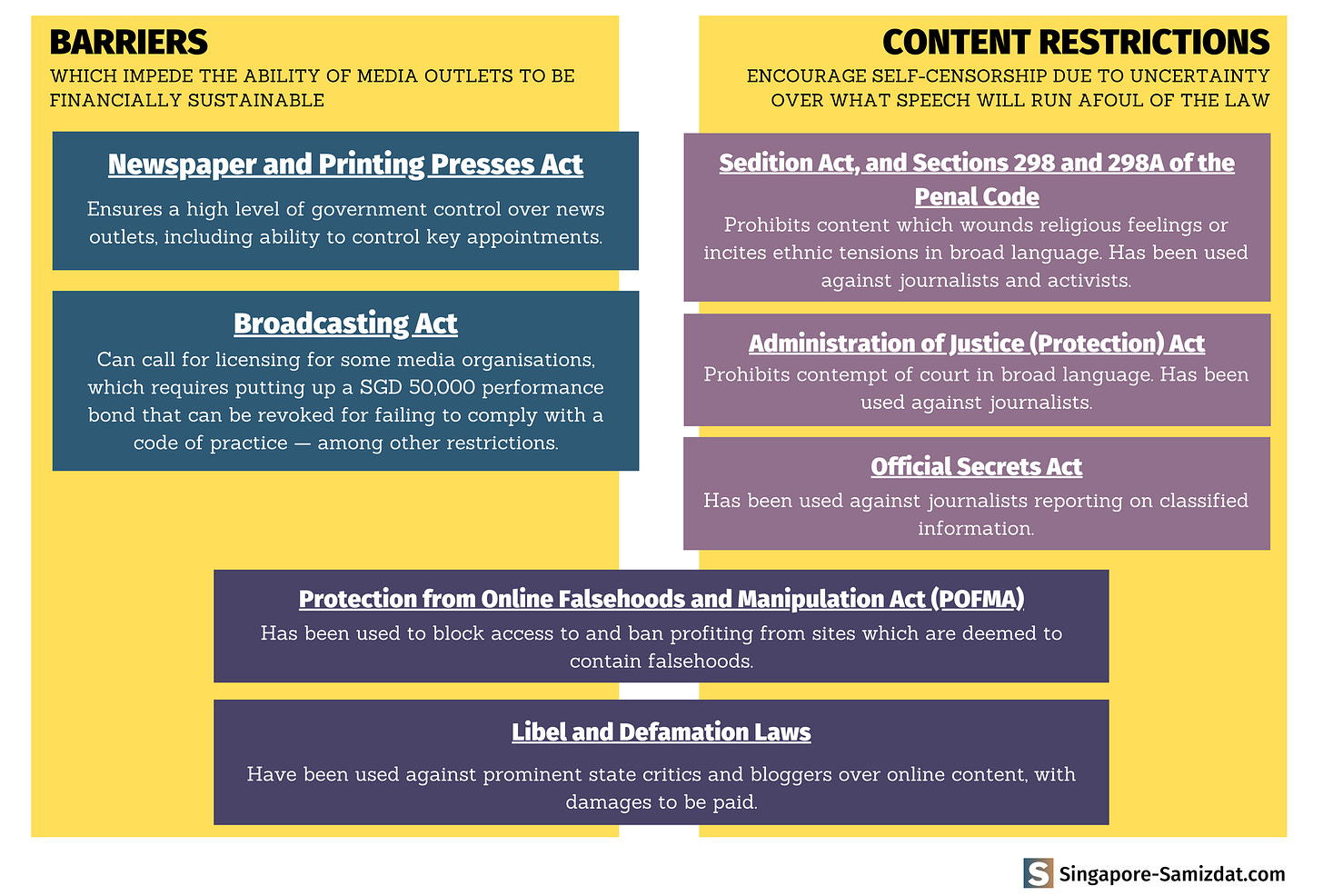

Singapore's press controls create a difficult environment for 'hard news' media outlets that are not affiliated with the state. To take one example, licensing requirements under the Broadcasting Act can create financial and operational barriers for new media startups.

Former Straits Times Editor Bertha Henson’s Breakfast Network folded after it was asked to become a class licensee under the Broadcasting Act. Becoming a licensee requires one to put up a 50,000 SGD performance bond that can be revoked for failing to comply with the Internet Code of Practice. Being a class licensee also requires an outlet to reject foreign funding. The Online Citizen was previously asked to return $5000 in advertising revenue from a UK-based group as it was considered a breach of license conditions.

When Mothership was asked to become a licensee, then-Managing Editor Martino Tan shared:

One of the considerations we had as we were mulling over the decision if we should comply was that $50,000 is a big sum of money for a small team like ours.

In this difficult environment, state-affiliated outlets like the Straits Times have continued to operate while some of its most promising rivals have floundered: a study by IPS in 2017 found that ⅓ of socio-political sites created after the 2015 General Election are no longer active (with The Middle Ground and Inconvenient Questions as some of the most noteworthy closures).

However, these strict press controls also harm state-affiliated media. Scholars have long argued that press controls — such as the Sedition Act, sections of the Penal Code, Administration of Justice (Protection) Act, POFMA and others — create a culture of self-censorship and self-regulation due to a high level of uncertainty over what content will run afoul of the law. Without even violating these laws, independence is undermined by self-censorship.

Though the mainstream media does not usually run afoul of such laws, they are far from immune. High-profile cases of the Official Secrets Act involved SPH journalists. POFMA was invoked against Channel News Asia and its coverage of comments made by SDP candidate Paul Tambyah during the 2020 General Election. Thus, despite few rivals for Singaporeans' interest in 'hard news', press controls likely place hard limits on the public's interest in and support for the mainstream media.

How do ownership controls limit experimentation?

Whereas in the pre-internet past, media outlets under SPH and Mediacorp enjoyed a pseudo-monopoly on news about Singapore, they now have to compete with a widening field of alternatives able to tap into more diverse sources of funding.

To take one example, Tech in Asia is a Singapore-based media outlet that has reported on Asia’s tech scene for more than ten years, and only recently turned a profit in 2019. Tech In Asia attempted many costly experiments and significant changes to its operations over the years, including a blockchain-powered content system and significant staffing changes to draw key names in the tech scene.

A 2017 investment from South Korean conglomerate Hanwha allowed the company to stay open as it struggled to find its footing. In contrast, state-affiliated media outlets such as SPH are less able to attract such funding, or to partake in costly experiments or drastic management changes, as the law governing newspaper companies ensures that the state always determines who holds the company's management shares — which have 200 times the voting power of normal shares.

With the state exerting such a high level of control over structural and staffing decisions, the room for fundraising and creativity is necessarily stifled. Indeed, SPH Chairman Lee Boon Yang stated that the new SPH's new ability to operate without the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act's restrictions means "greater flexibility to tailor its capital and shareholding structure to seize strategic growth opportunities". (Correction: The Ministry of Communications and Information clarified that the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act would still apply to the new SPH media)

For more stories on Singapore's internet, press and government, subscribe to receive email updates with each new issue's release.

Is the readership of SPH stagnating in the digital era?

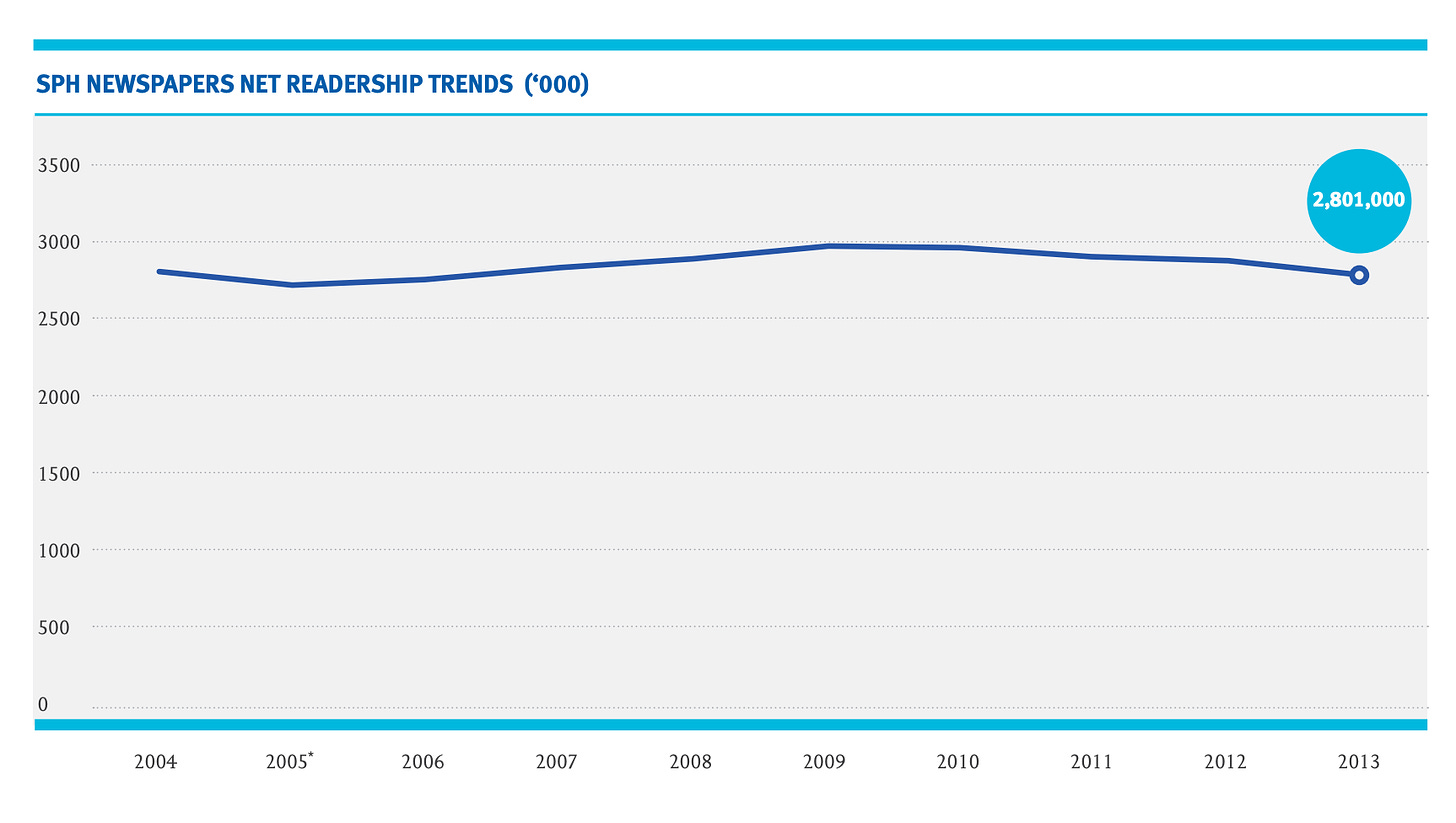

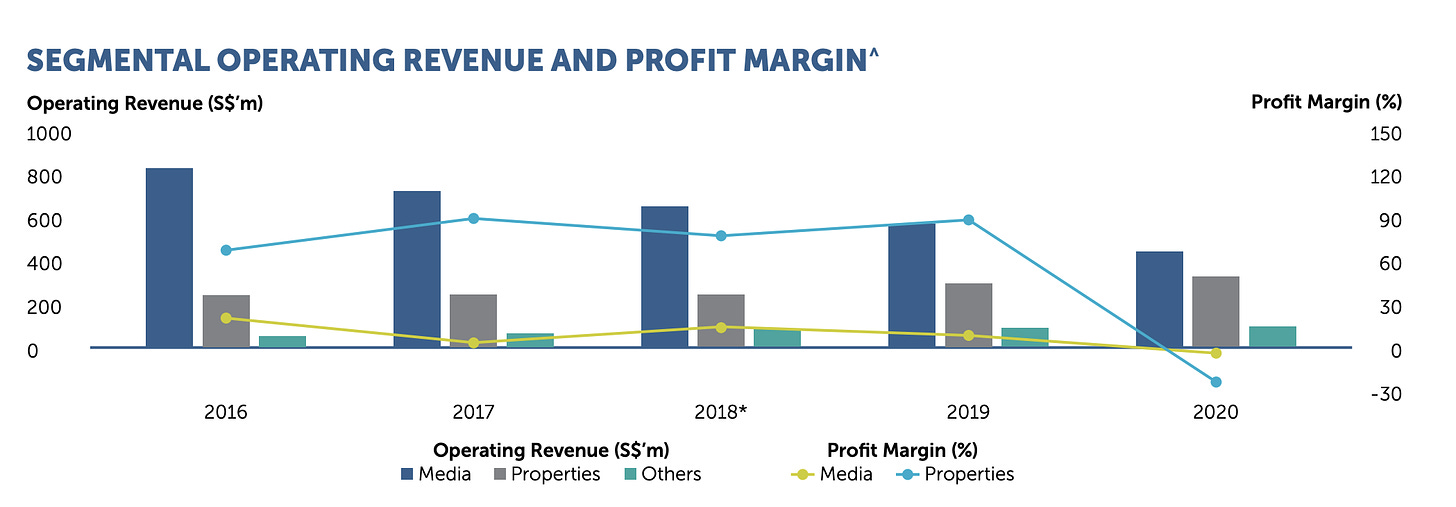

Available data from SPH points to poor growth in readership from the early 2000s (that peaked in 2009) and a slow transition to digital.

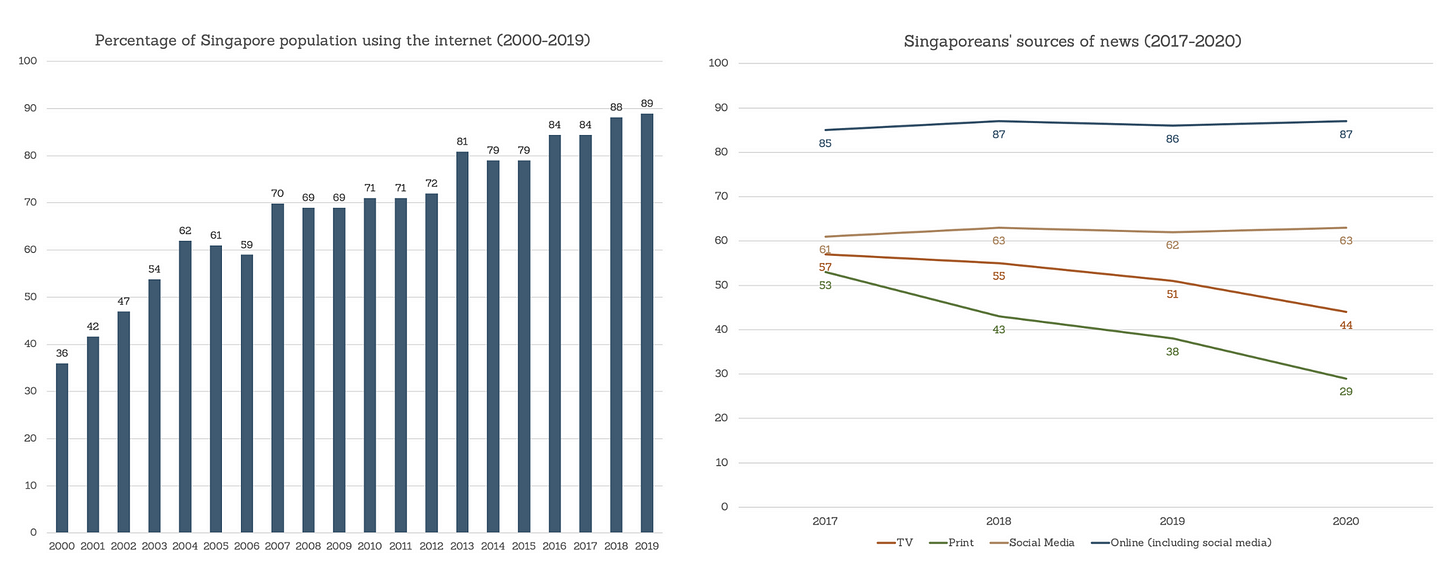

This stagnation seemingly coincides with the growth of internet access and the rise of digital news in Singapore:

The unprofitability of traditional media as we transition into an increasingly digital era is a global phenomenon. While paying for a physical newspaper subscription was once the (profitable) norm, nowadays, the vast majority of online users do not pay for news media. In Singapore, only 14% of those surveyed indicated that they paid for online news in 2020, a drop from the previous year.

Was COVID-19 the kiss of death for SPH?

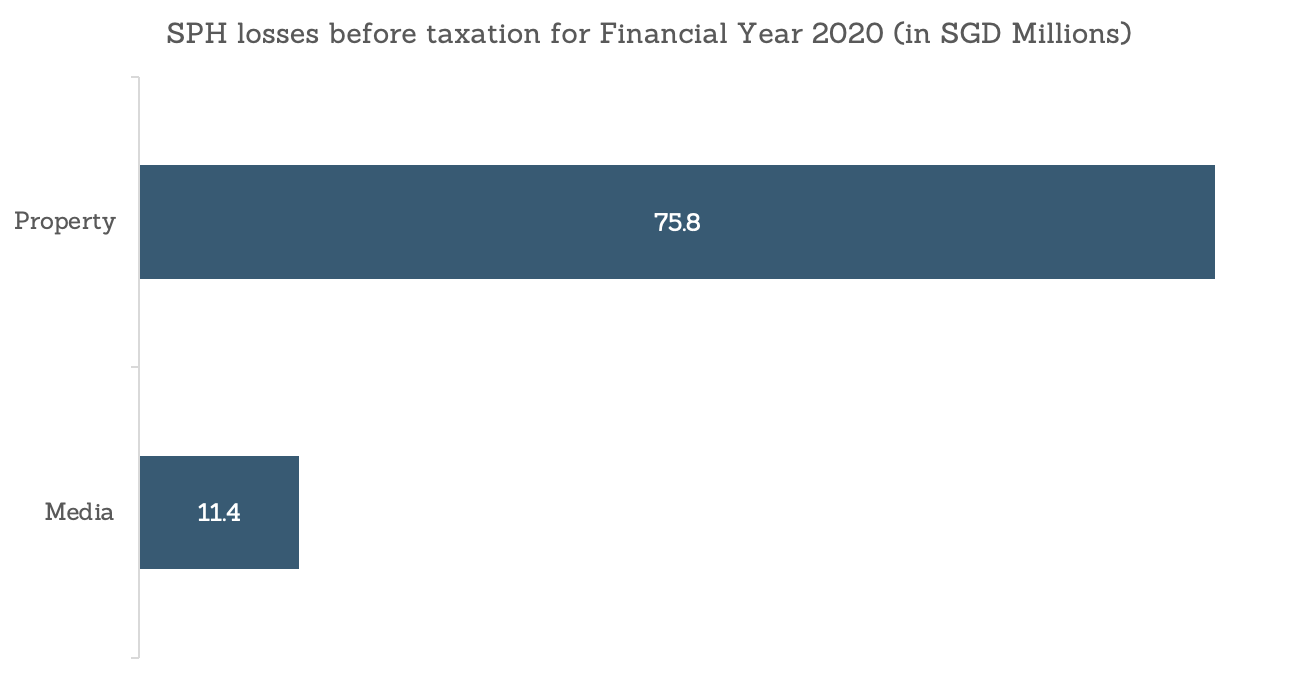

In 2020, SPH recorded its first net loss — of SGD 83.7 Million — due to the pandemic’s impact across its business holdings. While COVID-19 had a negative impact on SPH’s media business and its ability to draw advertisers, the greater impact was on its property holdings:

The most obvious financial change from 2020 was the drastic decrease in profit margins from both SPH’s media and property operations.

SPH’s property holdings include shopping malls in Singapore and Australia, student housing in Germany and the United Kingdom, and elderly care homes in Singapore and Japan. Such losses are thus an unsurprising result for a year in the grip of the pandemic, likely made worse by the time needed for the real estate and retail sectors to recover from the pandemic’s impact.

Was the pandemic the straw that broke the corporate camel’s back and triggered the restructuring?

What is the alternative to mainstream media?

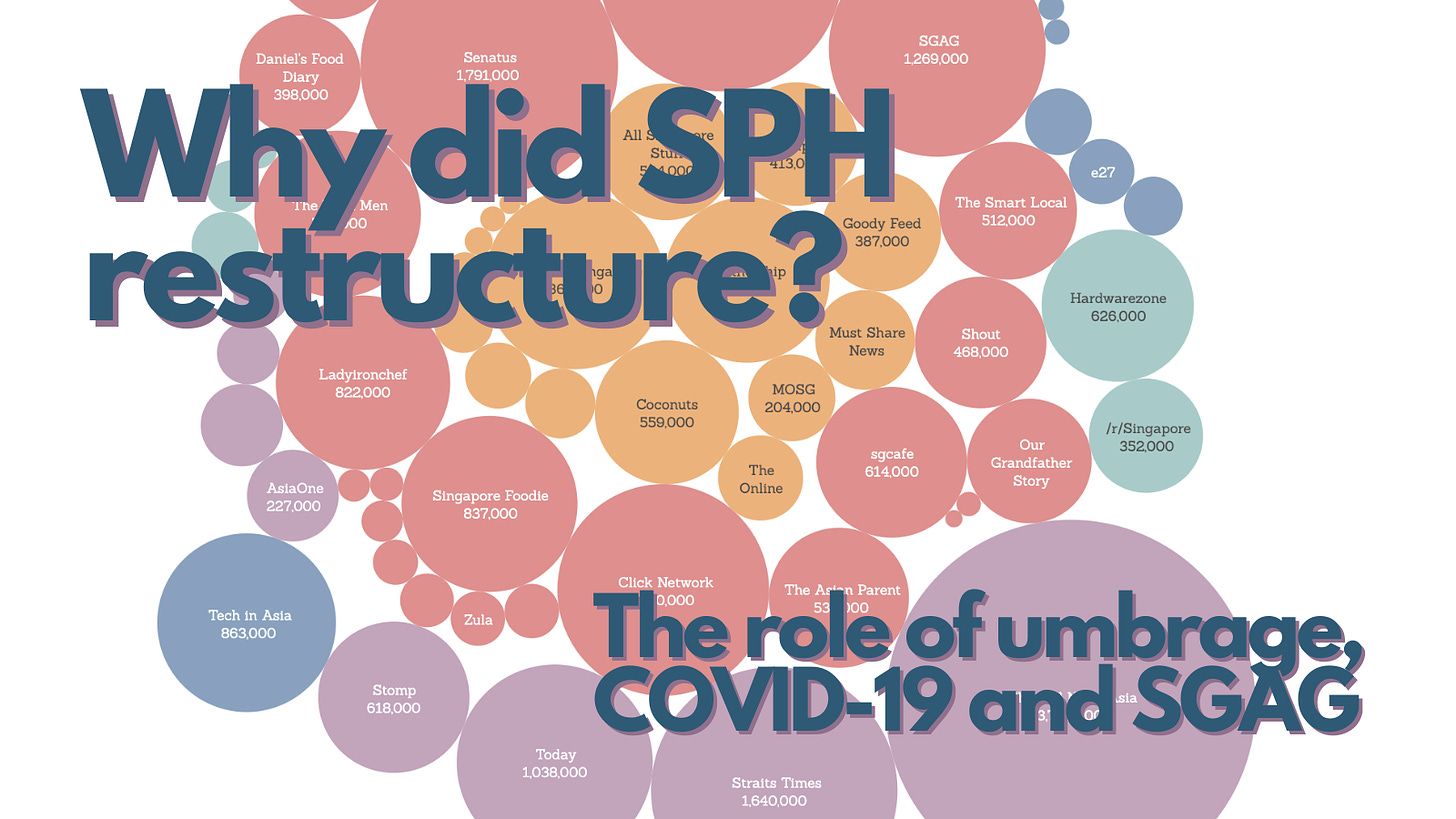

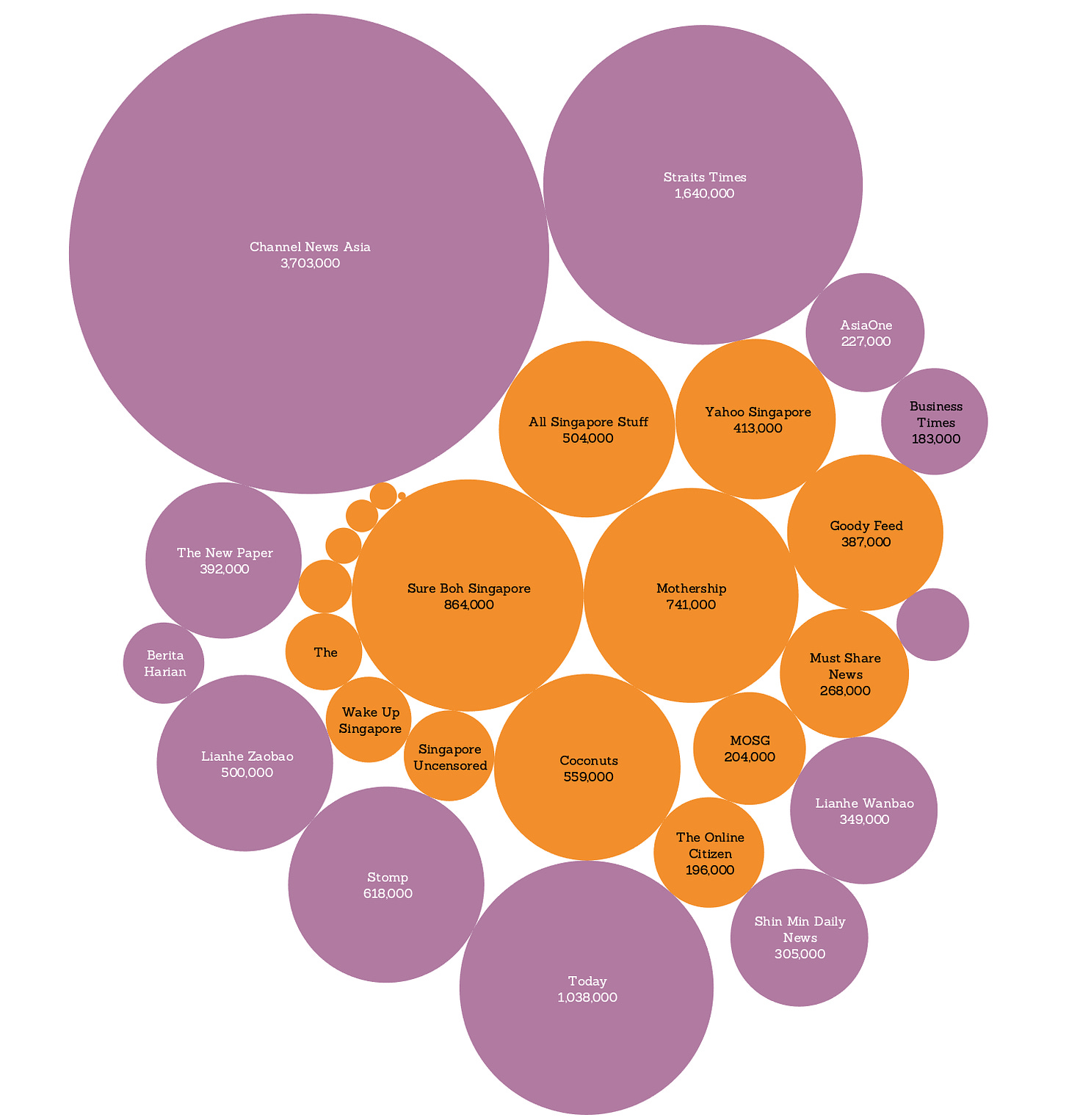

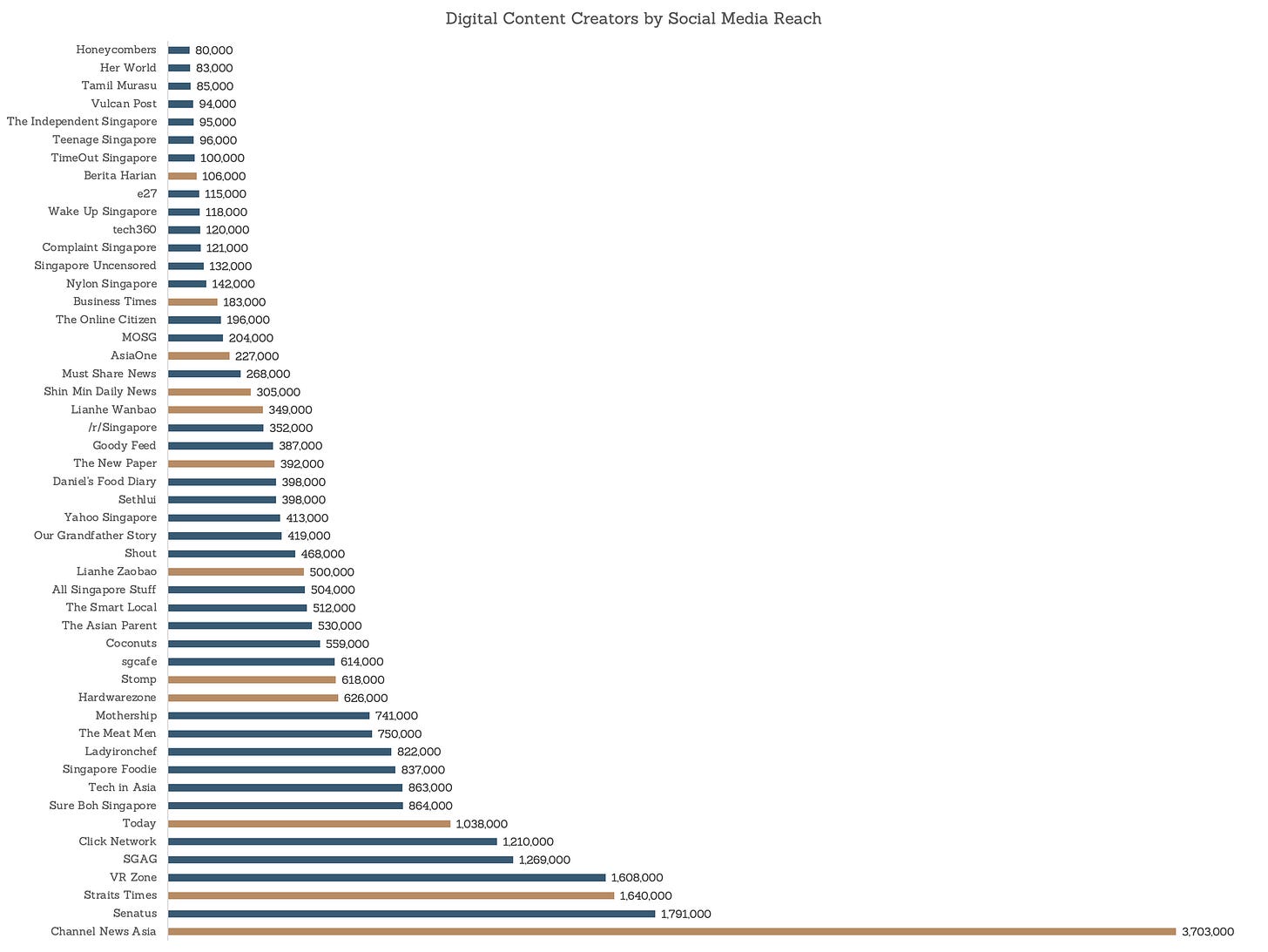

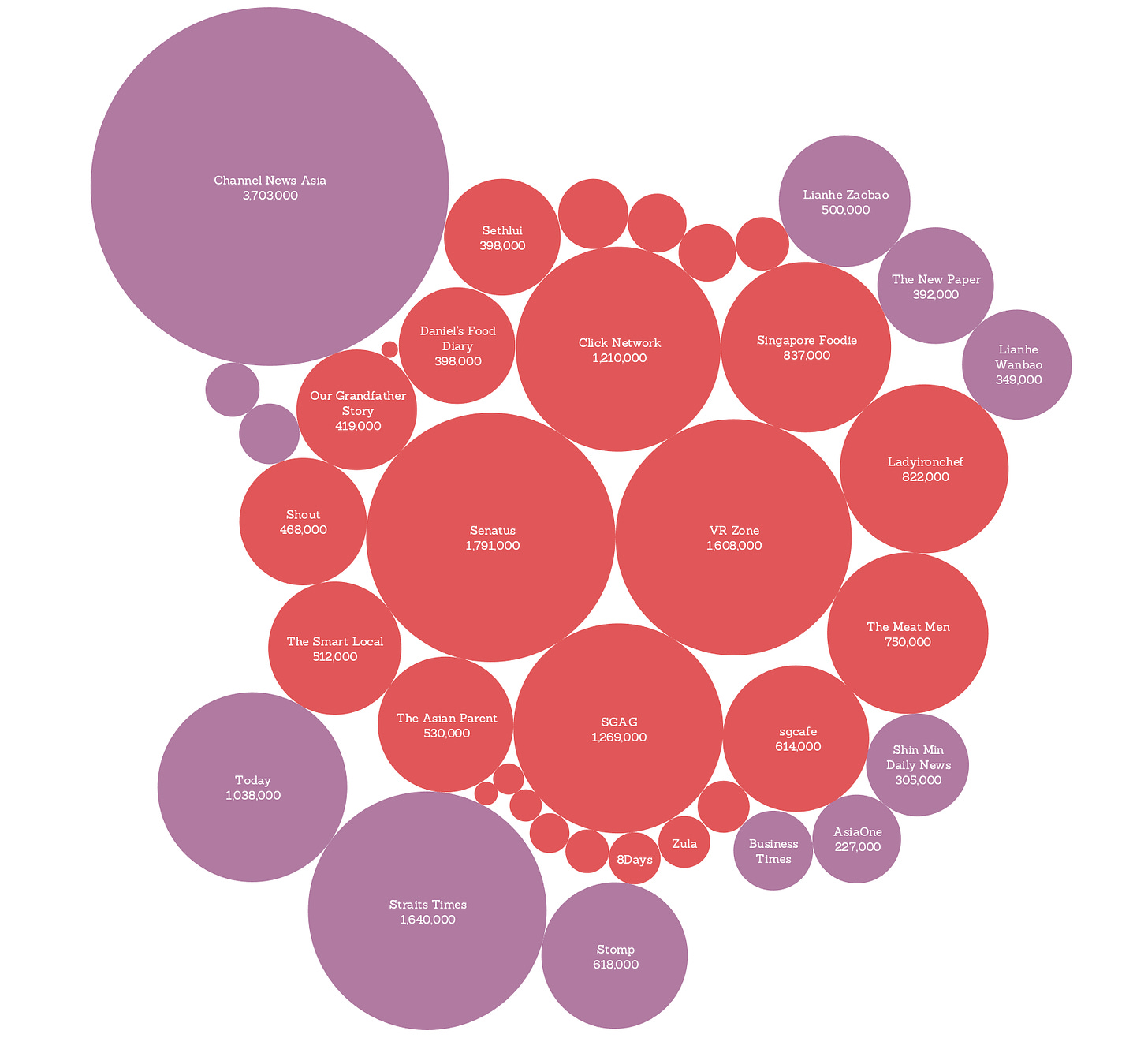

In terms of social media reach, outlets run by SPH and Mediacorp remain the most popular. However, many of the organisations which come close to rivalling them are internet startups — founded and operating exclusively on the internet.

As the space for ‘hard news’ has diminished, many new and existing media startups have responded by shifting towards ‘soft news’ through content with less emphasis on politics such as lifestyle or tech, or by moving towards content on social media.

Such content skirts around many of the financial constraints and press controls which create barriers for its predecessors: Inconvenient Questions has restarted as outlet which exists only on social media. Although The Middle Ground no longer exists, its spirit likely lives on in Bertha Henson's frequently recurring Chin and Chai Facebook posts. Outlets which do not have an explicit focus on news reporting seem able to evade the burdensome need for licensing which limits funding and creativity.

(Subscribe to Singapore Samizdat for more stories on the impact of social media on news-making, politics and more in Singapore)

Competition for native advertising

Beyond creators which focus on reporting the news, many of SPH’s new rivals are lifestyle or business brands with a strong digital reach and clearly defined audiences. This increasingly crowded field is likely to negatively impact SPH’s ability to draw advertisers — who seek certainty through increasingly targeted advertising, where less of one’s advertising budget is wasted on less relevant audiences.

In the lifestyle space, mainstream media has to contend with the likes of SGAG, Click Network and Mothership — with only Channel News Asia and The Straits Times beating them in social media reach.

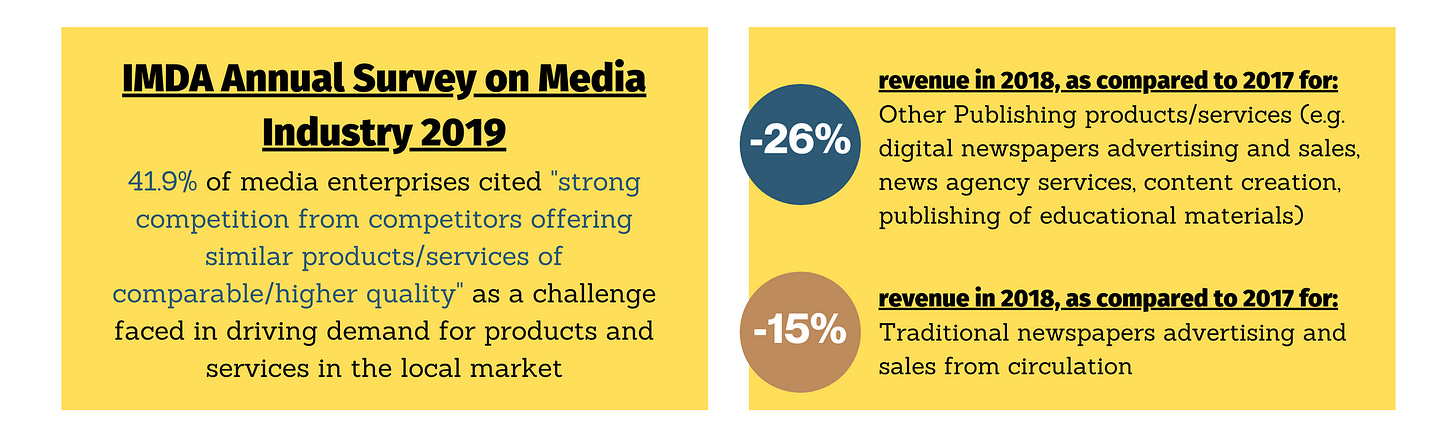

Reflecting this, the IMDA’s Annual Survey on Media Industry indicates that:

Indeed, the pursuit of valuable advertising money has pushed many organisations, both in Singapore and abroad, to increasingly use native advertising as a source of revenue. Also known as sponsored content, advertorials, or branded content, this form of advertising goes beyond traditional advertising in that it appears alongside editorial content and mimics its appearance. Unlike traditional ads, it is sometimes unclear that the organisation was paid to produce this content.

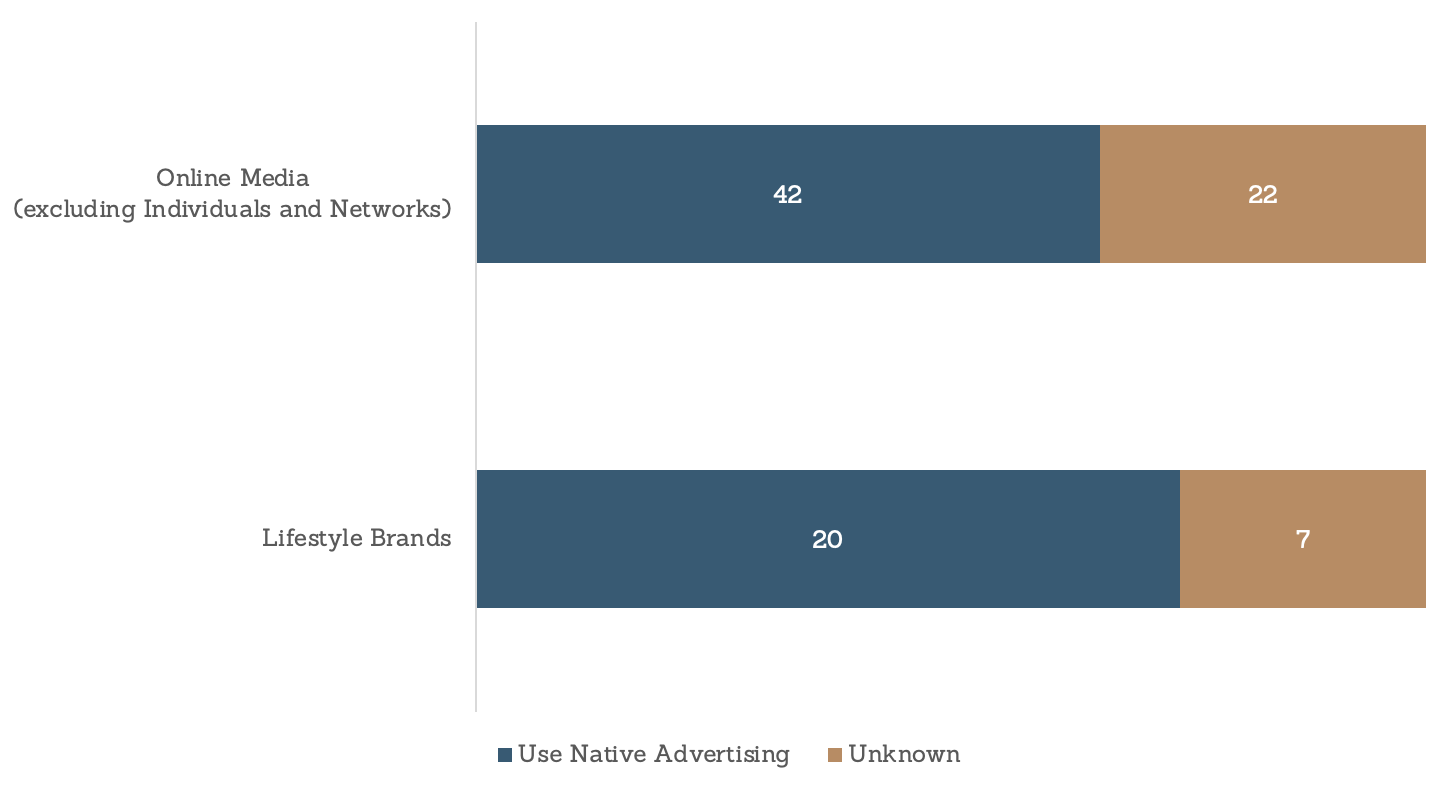

Based on an analysis of 64 content creators, a majority use native advertising:

While organisations such as the Straits Times and Mothership make clear what content was sponsored, there is no legal obligation to do so. The Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore does state in its code of practice that sponsored content should be distinguished from other content, but this code “seeks to promote a high standard of ethics in advertising through industry self-regulation.”

The unviability of other models of funding and the unregulated nature of native advertising may also be a potential explanation for the number of new media startups with a strong emphasis on branding partnerships, sponsored content and product reviews. Its prevalence should also set off warning bells about the level of (sometimes ambiguous) influence which commercial interests have in defining the content we consume on a daily basis.

The future of SPH

How will SPH respond to its stagnating readership, growing competition from other media outlets, and public perceptions of undue influence from government and commercial interests? Many have argued that SPH and Singapore's media regulations need important reforms before SPH can ever be a thriving source of independent journalism.

That the new SPH will be headed by former Minister of Transport Khaw Boon Wan likely goes to show that such reforms are unlikely, because for SPH: old is the new new.

For more stories on Singapore's internet, press and government, subscribe to receive email updates with each new issue's release.

Content creators by social media reach

The spreadsheet of content creators by social media reach put together for this article, accurate as of May 2021, can be found here. Social media reach is defined as the content creator's following on their most popular platform. All social media reach figures are rounded down to the closest thousand (or to zero, if lower than a thousand).

This is not a comprehensive list of content creators and media outlets in Singapore. Influencers and individuals are also not currently included. Inclusion on this list is not intended as an endorsement, and is meant to convey a sense of scale between content creators in Singapore. Have suggestions for more outlets which should be added to this list — or just suggestions in general? Reach out to me at teokaixiang@protonmail.com.

There are some caveats to this spreadsheet's use of social media reach as a measure of scale, in that it does not account for inauthentic users (bots, paid-for followers), the non-equivalence of users across platforms (1 Reddit subscriber does not equate to 1 Facebook like) and that not all of a page’s social media followers are based in Singapore.